Perth has been in a drought for the past five months, but the record was broken somewhat dramatically earlier this week, when we were hit by the worst storm in fifty years. The city centre was awash with rainwater and a hundred thousand businesses and homes lost power as winds of more than 120 km/h ravaged the city. Bronwyn was in the city when it hit, and watched as pieces of scaffolding were torn from a high-rise development. Judging that the train system would be inundated, she caught a bus, which turned out to be a lucky move. The emergency services had shut down most of the roads in the core because they were far too deeply flooded for normal traffic, but the rear-engined buses were big enough to get through, albeit by occasionally driving on the pavement. The police contacted the bus drivers by radio and told them not to let anybody off until they were well clear of the city. This was fine for Bronwyn but disturbing for some of the other passengers as they watched their flooded stops sail past in the wake.

In Australia it is fairly common that storms are accompanied by large hailstones. Down the eastern coast of the continent, hailstone damage to cars is so common that it is rarely remarked upon. Here on the west coast, though, its a bit of a rarity and this particular storm generated chunks of ice ranging in size from golf ball to cricket ball, smashing their way into houses through corrugated iron and tile, and destroying car windows and sun-roofs. The damaged houses, shops and cars then began to fill up with the torrential rain.

On the next morning I cycled to work before dawn as usual, and found the roads completely obscured by a blanket of branches, twigs and leaves ripped from the suburban trees.

Many of the trees, rooted in nothing but drought-dried sand, had given up the unequal battle completely and were lying embedded in the roofs of houses and across crushed cars.

Most of the lights and traffic signals were out, and abandoned cars were scattered at the bottom of the steeper hills.

Passing acres of car dealers in the business district, I was amazed by the extent of the damage. On some lots, almost every windscreen was cracked, and none of the body-work would ever be the same again.

One car drove past looking as if somebody had attacked it with a ball hammer.

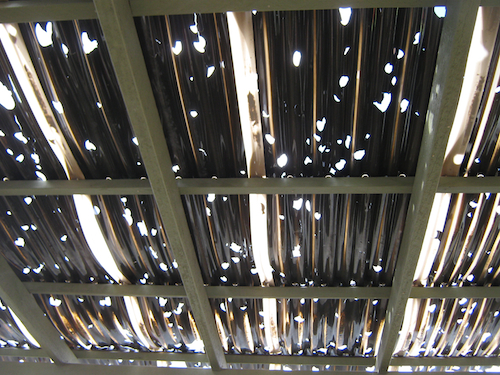

Once at work, I marvelled at the roof of our chill-out area, which resembled nothing more than a colander.

Out on my postal round, I found gardens littered with shattered roof tiles and glass. The glaziers were having a field day, simply moving up each street from one client to the next. Meanwhile the park rangers had arrived, equipped with chainsaws and cranes and chippers as they began the long task of extricating all the fallen trees without causing even more damage to the surrounding property. All around, the elderly and retired were doing their share, brushing the streets clear with brooms and, in more than one case, on hands and knees with a dustpan and brush.

Even the ants had changed their habits. When the rain hit, they must have scurried around looking for somewhere safe to put their queens and eggs, and most of them settled on the same brilliant idea; they’d move into the post boxes. Almost every brick box was teeming with insect life, usually emerging from a hole that they’d cut around the soft mortar where the house number had been formerly screwed in.

As quickly as the rain came, it ran away, either pouring down the roads and paths and into the river, or sinking into the parched sand. Business quickly returned to usual, albeit amid scattered buckets and with the remaining unbroken windows and doors open to air the carpets. The cars, battered and missing windows and sun roofs, are driven stoically to work in the blazing sun. A fire-sale begins on the car lots. And in the heat of the new day, I fancy that I hear the sound of a million pens, writing to their insurance companies.