Five in the morning, pitch black, nothing stirring in Canberra apart from a mismatched pair of four-wheel drive vehicles heading purposefully westwards into the Australian outback. Although we’d travelled quite widely in New South Wales, the south-eastern corner of the island continent, it is all comparatively lush, and we were keen on seeing some of this famous outback desert that wed been hearing about. However, the nearest example was about a thousand kilometres to the west, and although my modern air-conditioned Nissan could do it in comfort, Teun and Loes were in their twenty-year old Land Cruiser, the Wahoo, so we had to take it gently.

Wahoo!

Teun

After climbing out of the vaguely hilly bowl that forms the Australian Capital Territory, we rolled down to the flatlands of the Murrumbidgee River and the town of Narandera. Every small town in Australia struggles to be the home of some unique feature, whether it be the biggest merino sheep in the world (made of concrete, in Goulburn), or the biggest trout in the world (made of fibreglass, in Adaminiby), or the oldest continually licenced premises in Australia (one of at least three similar claims that we have found, this one in Berrima). Narandera is no different. As we turned onto the arrow-straight Sturt Highway, road signs sternly admonished us that we had missed the opportunity to see The Largest Playable Guitar In The World.

We were the only vehicles on the highway. Ahead of me, all I could see were the dull red tail-lights of the Wahoo, and a bright blue backlight on Teun’s dashboard, which appeared somewhat bizarrely to be a GPS navigation system. I made a note to ask him about it later.

Dawn rose in the rear view mirror. The night slowly faded to grey and then fled into the usual gorgeous blue of another perfect Australian day. The occasional trees on the horizon became shorter and stubbier, the earth by the side of the road became noticeably redder, starkly contrasting with the green of the grass being grazed by the thin and hardy Australian sheep.

The road continued on, and on, ever westward, past another sign proudly proclaiming that we were driving through The Best Wheat-Growing Country in Australia. Back in lofty Canberra, the days had been getting mild, even a bit chilly, but out here on the plains we started slathering on the lotion as the morning sun scorched through the open sunroof.

Six hours in, I needed a coffee, so we pulled over in Hay, pretty much the only town on this part of the Sturt, and stoked up on the things that we thought we needed; several pints of caffeine, some baling wire, a roll of gaffer tape, and a spade. Remembering the glow of the Wahoo’s navigation computer, I asked Teun for a demonstration. He looked somewhat sheepish as he showed me the screen. He’d forgotten to load in the map for this part of Australia, so the screen showed a huge featureless field of blue with a small “you are here” cursor flashing in the centre, and far far off at the bottom of the screen, a little dot that said “Melbourne”.

Actually, back on the Sturt, driving across the endless red terrain, that felt about right. Emus wobbled humorously by the side of the road. Hours passed. Finally we arrived in Balranald, the last fuel station before the Mungo and the point at which we finally left the Sturt and headed north.

The Sturt Highway

Exactly 53km up the road toward Ivanhoe, according to the directions we’d found on the web, we turned left onto a sandy track. Loes compared it to Africa; beaten sand, low scrub, and emus running here and there in the bush. I gave the Nissan its head, hammering down the trail at 140kph, blowing away the cobwebs of the miles and miles of tarmac, finally arriving by the public lodges in the Mungo National Park. According to a sign on the door, in order to get the key we had to telephone the Parks office. When I called them, I got an answering machine; the office was closed.

On, then, to the camp site, which had an honesty box system for the pitch, and another one for firewood. We had no tents as such, but we’d come prepared to sleep in the vehicles if necessary. While Loes unloaded the Wahoo’s excellent cooking range and rustled up a meal, the rest of us cracked some welcome beers and got on with some vehicle maintenance. One of my tyres was running a bit bald and needed replacing, and Teun needed to pump diesel out of his second fuel tank because it didn’t seem to be properly connected.

A superb dinner, then a fire, more beer, wine, laughs. It was the first time I’d burned Eucalyptus gum, and I was impressed. The bark makes excellent tinder, and the wood itself is incredibly dense, lights easily, burns hot but slow with no smoke or spitting, and then settles down to perfect red embers.

A comfortable night in the cars, then up with the birds – particularly the cheeky Apostle birds which had their noisy beaks in everything – and onto the circular track around the Mungo National Park.

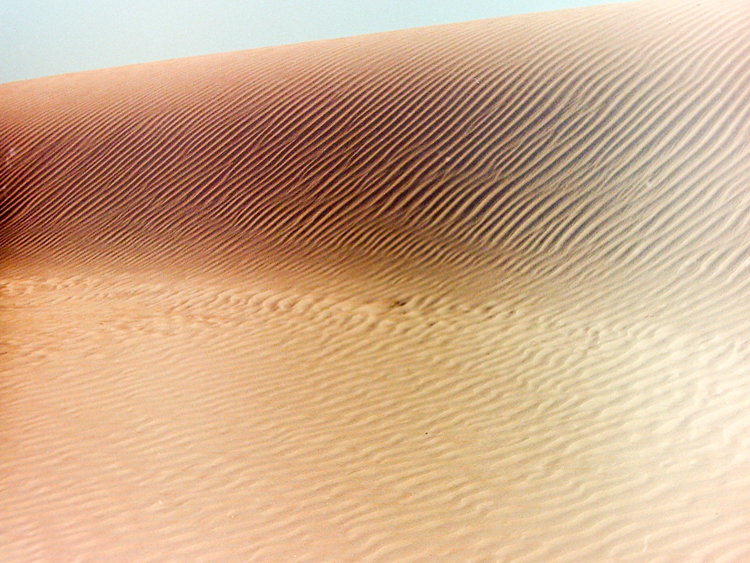

First stop, the amazing Walls Of China, an enormous lunette dune stretching from horizon to horizon and moving slowly across the outback at several metres per year. At its leading edge, it slowly smothers the scrubby bushland. At the other end, thousands of years later, it spits out all the things it has consumed; kangaroo bones, the remains of aboriginal fires, the odd artefact. As it moves, it carries with it a population of contorted Bluebush whose roots hold it together as the wind sculpts and ripples its upper surface.

The Walls of China, lunette dunes of Mungo Desert

A wedge-tailed eagle soared above as we took the cars up a small track over one end of the dune, stopping to wander through the extensive complex of beautifully carved gullies formed by the heavy water erosion of the hard-packed sand.

Beyond the dune is the Mallee, an area of unusual multi-stemmed eucalypts indicative of the most dry and barren conditions. There was, however, still plenty of life to see, from the beautiful emerald green Mallee Ringneck parrot to the myriad red and grey kangaroos hopping over the red red earth under the startingly clear blue sky, pausing now and again to stare at the metal interlopers into their domain.

Roos in their natural habitat

The mallee part of the national park is just as interesting as the lunette, home to specially adapted birds, lizards and plants, particularly the rather astounding Porcupine Grass, probably the sharpest and most uncomfortable ground cover in the world. It is dotted with huts and tanks left over from various attempts at grazing the arid land, including the interesting Round Tank, which had been completely fenced in with a small access ramp leading to a steep drop down to the water; in fact it was a trap for wild goats, a pest in this area, which could jump down to the water but which could not then get out again. A scattering of skulls were testimony to the efficacy of the system.

Finally, as the end of the weekend drew near, it was time to head back to Canberra. Before we left, we climbed up to the Mungo Lookout, where the full extent of the bluebush scrub was visible from horizon to horizon, all the more astounding because when the settlers, who were the source of all the abandoned buildings and sheep stations that we had seen, were trying to make a living here, all this was just a huge lake.