The bush toward Kambalda is starkly beautiful, with the bright red of the soil contrasting with the luxurious and brilliant greens of the gum trees, low-growing scrub, and ground-hugging succulents. Whatever its size, each plant is surrounded by a circle of bare earth representing the area from which it is sucking precious water. No competing plant can gain a foothold inside this zone.

The land is largely flat and often salty, broken only by the small hummocks of laterite gossans, interesting geological features that form after iron is leached from the soil, forming a hard protective cap that prevents the underlying rock from being eroded away over the millennia.

A little out of Kambalda there must have been a recent major change in the underlying hydrology, because for miles and miles all the trees had been reduced to bone-white sticks. I wondered if one of the many mines in this area had redirected some underground waterway into its workings, or if perhaps there had been a series of particularly dry seasons. Whatever the underlying cause, the water source seemed to have now returned, because a new layer of lush growth was springing from the base of each apparently dead tree trunk.

The road trains are longer out here; over fifty metres. If they’re coming toward you with a following wind, their bow wave can get quite uncomfortable.

We saw our first bit of road kill, but it was thoroughly tenderised and it wasn’t obvious what it had been. Certainly not a marsupial; maybe some kind of deer? Then we realised that there were feral goats grazing In the bush, some with horns as long as my arm. We also startled an escaped sheep, definitely of domestic vintage, but unusual in that it had retained a full tail, a very impressive sweeping arm with a fluffy pom-pom on the end.

The road went on, the earth became lighter in colour, but the signs to distant mines remained as prevalent as ever. We started to see what were apparently vast flats of soft mud, which ultimately joined together to form a feature called Cowan Lake which is mined for gypsum. I didn’t quite dare try to ride the motorcycle across the inviting flat surface, but clearly a number of cars had already been doing circle work and they hadn’t made much of a dent in the hard-baked clay pan.

Suddenly we were in Norseman, where a sign warned that it was 198 km to the next fuel stop (one full tank of fuel for us), and that water was scarce from now on so that we must be sure to fill up before continuing. I wanted to investigate an intermittent knocking from the bikes drive chain and there seemed to be plenty of motels to choose from, so we stopped for the night.

I quickly traced the knocking sound to the chain adjusters which had come loose. Fixing the problem meant loosening the rear wheel nut, and unfortunately some lazy mechanic seemed to have thrashed it on with a windy-gun instead of tightening it by hand. I hate it when they do that, as it makes roadside adjustments really difficult. Still, there were plenty of heavy rocks lying around, and by hitting it repeatedly I finally got it undone. We had booked in to the motel restaurant for dinner, and it was made quite clear that if we booked for seven, then weren’t expected to show up until seven. With an hour to kill we took a stroll around the town, which consisted mainly of a scattering of hundreds of small houses in various states of disrepair, all apparently servicing the Norseman gold mine.

The mine – and the town – have an interesting history, in that they were named after, and discovered by, a horse. The story goes that a prospector tied the horse to a tree by his brother’s tent for the night, and when he woke up he found that the horse was lame. Investigation revealed a large chunk of gold-bearing quartz lodged in Norseman’s hoof. The prospector and some friends got together and purchased the claim, and the town came into being on the site.

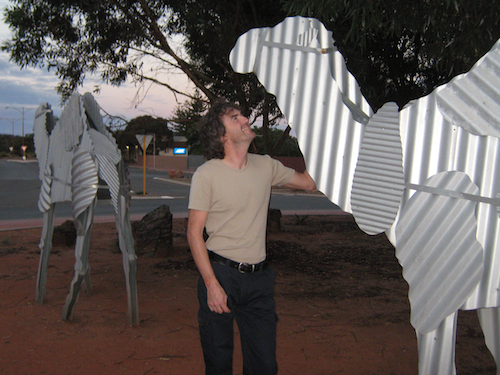

We wandered deeper into town, admiring the famous collection of galvanised iron camels built on the roundabout in the centre.

After a little more searching we finally located what seemed to be Norseman’s only pub, and met the locals. Both of them. One sat and drooled quietly onto the bar top, while another attempted repeatedly to engage us in conversation, which might have been interesting except that he had a habit of staring up into your eyes from close range, really foul breath, and a brain that seemed to be full of little more than whirring butterflies. Quickly finishing our beers, we scuttled back to the motel.

Since it was still too early for dinner, we decided to sit on the verandah of the restaurant and enjoy a pre-prandial bottle of wine. This suggestion caused great puzzlement to the waitress, who became fixated on the idea that we wanted to cancel our dinner reservation, but eventually we sorted it out and chose a bottle of elderly Margaret River Cabernet Sauvignon that seemed oddly out of place in the otherwise standard selection of cheap table wines. The waitress struggled with the cork for a very long time, until I finally realised that she hadn’t even managed to get the point of the corkscrew into the wood, at which point I gently suggested that I give it a try. The bottle was thrust into my hands with alacrity, and I realised that all the others on the shelf were screw-caps. Possibly she had never before wielded a corkscrew in anger; I began to wonder just how long those bottles had been sitting there.

The wine turned out to be very good indeed, and we sat and chatted in the twilight until our food arrived. We hadn’t expected a great deal from the dinner, but even so we were still a bit surprised when my otherwise acceptable steak came with a big dollop of instant mash, and Bronwyn’s bruschetta came smothered in a slab of melted cheddar. Still, the wine was good and there was another bottle left, so I went and fetched it from behind the bar, snaffling the corkscrew on my way back to the table.

After dinner, we met Anne, our neighbour at the motel, who was travelling in the opposite direction to us. She had a bottle of white in her luggage, and we had a bottle of champagne in ours, so we got out some chairs and whiled away the rest of the evening on the verandah outside our cabins. We asked her what the road ahead of us held in store, and it turned out that her trip so far had been almost biblical, with plagues of mice, plagues of dragonflies, and a bushfire to contend with.

Out on the road next morning, we quickly found that Anne had been right about the dragonflies. Since they’re aquatic creatures, we weren’t entirely sure what they were doing out in the desert, but they slammed into the bike with dire regularity, to be picked off by cheeky crows whenever we stopped.

On the way out, we paused to gawk at the tailings heap from the still profitable gold mine, and then – watching out for flaming rodents – we rode on into the sunrise.