We’d been waiting in Apia, Samoa, for a guy who we’d arranged to take us kayaking. After some considerable waiting (most of it our fault and anyway very enjoyable), he materialised in the form of a Swede, Matz, who loaded us into his elderly jeep and took us to a beach on the eastern end of the island.

The Eastern side of Samoa

Here, amongst hundreds of smiling holidaymakers, we launched the sea kayaks and paddled out into the lagoon.

Matz and Bronwyn, almost ready to leave

We soon left the crowd behind. To our left, traditional fale appeared along the shore, against a backdrop of palm trees climbing the flanks of the mountain at the centre of the island. To our right, the sea smashed violently into the invisible reef, breaking into furious surf which petered out suddenly without disturbing the glassy smoothness of the lagoon.

The surf roared harmlessly only metres away on the other side of the reef

The kayaks seemed to float above the ethereal water

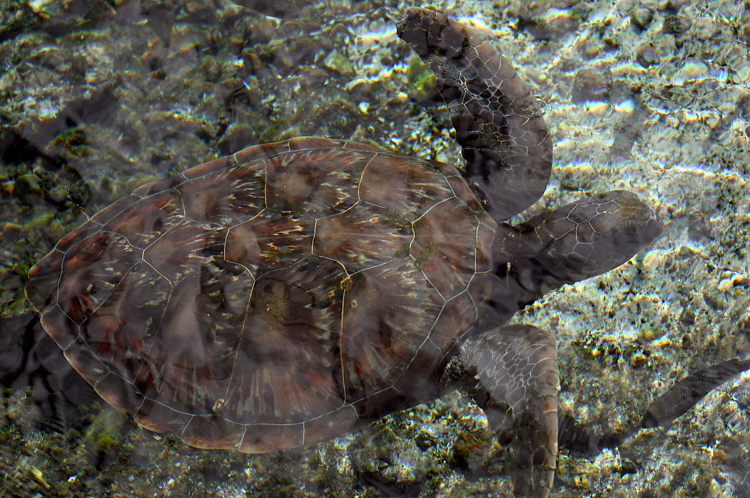

One hour turned to two as we paddled into a mild headwind, and the small island that was our destination grew imperceptibly closer. We were beginning to feel tired when a green turtle popped its head out of the water. Suddenly we realised that they were everywhere, several feet across, heads nervously popping up, spotting us, and then diving quickly away.

Hello, Green Turtle

We beached the kayaks on the small island of Nu’utele which boasted a handful of waterside fale, owned and maintained by a village on the mainland. Each fale was an open-sided wooden platform with woven palm-leaf blinds around the sides. The idea is that you roll the blinds up or down to create a through-draught depending on the prevailing winds. However, the villagers were expecting bad weather, so they had tied a tarpaulin to the windward side for additional protection. As it happened, this turned out to be a bad idea as the night was hot and still; in the early hours of the following morning I heard Matz untying his tarpaulin to get some air, but I couldn’t summon the energy to do ours.

Fale on Nu’utele

The traditional Sunday meal is a roast made over a fire in a cooking hole, and dinner comprised the remnants of the villagers’ own repast along with servings of parrot fish. We’d never seen parrot fish on the menu before; they are skinny blue things only about ten inches long and don’t exactly have a lot of meat on them, so we were curious to see how they were going to be prepared. We were a little surprised to discover that each fish had been braised whole, and then simply chopped in half, giving you the choice of either head end or tail end.

Shortly before sunset, the quiet, self-effacing villagers climbed into their boat and putt-putted to the mainland. A few minutes later, we heard a long honking noise from the far shore, the way I would imagine a conch-trumpet to sound, and a little later the Sunday evening service started. The congregation must have been on the beach opposite us, because the amplified voice of the priest echoed across the water, interspersed with Hallelujah!s and applause and singing. We couldn’t make out what he was saying, but he was obviously a skilled orator, switching from what seemed to be fire and brimstone haranguing to poetry and song and back again with consummate ease. Meanwhile, on Nu’utele, the bugs had started biting, so we retired with a paraffin lamp to our mosquito-netted fale, and listened to the wash of the waves on the beach only a few metres away, the thunderous boom of surf on the reef farther out, and the hypnotic sounds of the amplified priest across the water.

Paradise and a mosquito net

In the morning we were awoken by the sound of the returned villagers sweeping the beach of fallen banana leaves and accumulated debris. Their life is in no way primitive; it is simply traditional, an important distinction. For instance, although our fale was constructed mainly from coconut-trunk spars and woven palm leaves, the cross-spars in the roof were made from pieces of shipping pallet, and the banana leaves were sewn together with string and what appeared to be magnetic cassette tape. As well as the tarpaulin used in bad weather, each fale also boasted a small corrugated iron cap. This motif was repeated wherever we went; the traditional methods were preferred, but if some modern invention could do the traditional job better, then it was used instead.

We paddled out along the reef break to the next island, crossing a rather turbid channel with quite a noticeable rip, and ran the kayaks up onto a coral beach. Steps led up to an automatic lighthouse, from which we watched boobies and frigate birds gracefully riding the breeze. After a brisk swim in the surf, eerie with the never-ending pounding of the reef break just a few hundred metres away, we returned to the fale for lunch.

Good to be behind the paddle again

On the journey home, Matz and I decided to go out through the break into the open sea. This was an awesome experience, for the channel was only about ten metres wide, and on either side the rolling surf built up to an enormous height before crashing thunderously on the reef below. It was a strange feeling indeed to watch the tubes form and the waves rear high above on either side, while we bobbed reasonably placidly on a piece of lightly choppy ocean between them.

We were just about to turn around and go back in, when a large leathery green turtle surfaced right in front of me. Looking out to sea, it had no idea that I was right behind it, and I held my breath as it paddled slowly along with its enormously elongated front flippers. Unlike its smaller brethren, when it finally did see me, it didn’t swim like hell, it just floated gracefully down to a metre or so under my boat, a stunning view through the crystal clear water.

Back on shore, we had an interesting ride home in which we ran first out of diesel and then out of coolant, necessitating some roadside bartering to keep us on the road. Matz finally dropped us at the Millennium, where a porter whisked away our ragbag sacks and bundles and installed them in our room, where we leapt into the shower.

It was Bronwyn’s birthday, and a taxi was waiting to take us to Apia’s top restaurant, Sails, nestled amongst the churches on the waterfront. On the way out of the hotel, Bronwyn got waylaid by a receptionist who wanted copies of our passports or something, but I carried on outside to make sure that the taxi was still waiting. Sure enough, there he was, so I got into the back and explained that we needed to wait for my wife. He smiled and nodded his head vigorously; “Wife,” he said, and started the engine and drove off. Suddenly realising that he hadn’t understood a word that I’d said, I opened the door and bailed out.

The car stopped, and there was a pause. The driver slowly unfolded himself from the driver’s seat and stared across the car roof at me, until a delighted smile broke out across his face and he erupted into peals of laughter. “Your wife! Your wife!”

Once we were both safely installed, he drove us the kilometre or so back into town and decanted us outside the restaurant. Sails bills itself as The Last Restaurant in the World to Close, Every Night, a commentary on Samoa’s proximity to the dateline that had already caused us so much confusion (A couple of days later, we found ourselves in the bar of the International Dateline Hotel in Tonga, which bills itself as The First Bar that opens in the World).

Our table at Sails turned out to be the best in the house, out on the veranda overlooking the harbour sunset. The margaritas were excellent, and the food was astonishing; to taste their Commodore Sashimi alone, it is worth travelling halfway around the world.

Sunset from the balcony at Sails, Apia