Oslo to Bergen

The train from Oslo to Bergen is famed for being one of the most picturesque journeys in the world. The train stops often on its way up into the mountains, picking up passengers from the outlying regions of Oslo, and then settles in for the long and beautiful haul along the granite spine to the coast. I have done the trip before, and wanted to show it to Bronwyn, as it seemed like a great way to celebrate our wedding anniversary. However, this is the electronic age, and half the passengers in our carriage closed their window shades to concentrate on their laptops instead of looking out of the window. The two guys closest to us carefully occluded half of our view by closing their blind, and then packed up their computers and went to the buffet car, possibly to drink beer and watch the scenery go by, leaving the rest of us in the dark. It took some judicious seat-hopping, and a certain amount of hanging out of the door windows, to appreciate our journey.

On the lower slopes, hay fields scattered with occasional wooden cabins were punctuated by tiny villages and towns clustered along rivers, each community widely separated from the others but always painted bright colours, usually red or yellow.

Stunning views from the Oslo-Bergen train

After several hours of climbing, we attained the snow-line. Here again there were scattered cabins, but between and among them was nothing but scattered and shattered rocks, with only the occasional bowl of summer snow. Presumably these places are unusable outside of the winter months. The few towns are given over to skiing, but in November they were not yet open for business, although the pistes were being mown in preparation.

Shattered landscape above the snow line

Impressive melt-water waterfalls sprang from the dark granite as the train plunged through tunnel after tunnel, some bored through solid rock and others constructed from sturdy timber as a defence against avalanches. Melt-water lakes, some already re-frozen, sat amid a lunar landscape. Very beautiful.

Finally we arrived at our destination, Myrdal, at the top of the world, where the famous Flåmsbana train waited to take us down to sea level. Privately run, this is the steepest non-cog train in the world, dropping 864 metres in 20 kilometres of beautiful switchbacks.

Myrdal

All aboard the Flåmsbana!

The genial conductor pointed out some of the finer views, and suggested that if we moved to the disabled compartment, there was a window that could be opened for a better view without exposing the other passengers to the 6 degrees outside. As we dropped into the first incline, we caught a glimpse of the Rallarvega, the mountain trail from Myrdal to Flåm which we intended to walk later in the week. About half way down the valley, the train stopped for a few minutes so that we could get out and admire the thundering Kjosfossen waterfall.

Rallarvega

Kjosfossen

As the track flattened out into the valley above the fjord, we descended into cloud, and when we emerged from the bottom it was dusk. The tiny but beautifully formed town of Flåm spread out before us, and we stepped out of the train onto the quayside.

The building in the middle is the Marina Apartments, where we stayed

Eating in Flåm

We moved into a lovely little apartment overlooking the fjord. We’d felt lucky to get the apartment at all because both of Flåm’s hotels had said that they were full, only their most expensive suites were available, but in the event it turned out that they were actually empty and running on skeleton staff for the off-season. It was the same story with the restaurants. The receptionist at the Fretheim needed to see our reservation, so we tried the other restaurant in town. There was nobody there until we tried the kitchen where we found a surprised waiter chatting to his girlfriend, but we dined very pleasantly on catfish in black butter sauce. On another evening we made a reservation at the Fretheim, to find of course that we were the only diners, although the salmon tartare and venison in red wine were delicious. Both restaurants were operating on a two-dish menu which would not change for the off-season, so we were doubly glad that we had a fully equipped kitchen in the apartment.

Pink champagne on our balcony. It was cold, OK?

We never tired of the ever-changing view from our apartment

Flåm and Old Flåm, looking back after climbing up to Bekefoss

A cruise down Naeroyfjord

One morning, we took the local bus to Gudvangen, involving a 5km tunnel to the top of the pass and then an 11km tunnel back down to sea level, in order to catch the ferry back to Flåm. The point of this was to see the Naeroyfjord, designated a World Heritage Site because of the unspoiled beauty of its fjord terrain. We were very lucky that the sun had boiled off the cloud layer and although it was very cold, we sailed under a clear blue sky. The scenery was breathtaking, not least because of the crystal clear reflections of the mountains in the water, disturbed into surreal shapes by the waves of our passage.

Naeroyfjord reflections

Distorted Naeroyfjord reflections

Disturbed by our wake

A passage in Naeroyfjord

Undredal

Aurland

Before the mast

Hiking from Myrdal to Flåm

One morning we took the Flåmsbana back up to Myrdal, so that we could walk back down again. There is a trail, the Rallarvega, which was originally built by the navvies who were building the railway, but which is now mainly used as a precipitous mountain-bike trail. Years ago, while back-packing in this area, I had hiked down this trail and still remembered the experience with fondness and awe, so I was keen to introduce Bronwyn to the experience.

The main line to Bergen goes right, the Flåmsbana goes left (and down…)

Myrdal, at the top of the Rallarvega

The Rallarvega starts its downward plunge

Bronwyn and waterfall

Reinhard and waterfall

The views are fantastic, and the sheer scale of the vertical cliff faces that tower above is enough to make you feel utterly insignificant and so very privileged to be there, crawling like an ant down the face of the glacial valley.

Photos can’t do justice to this wonderful place

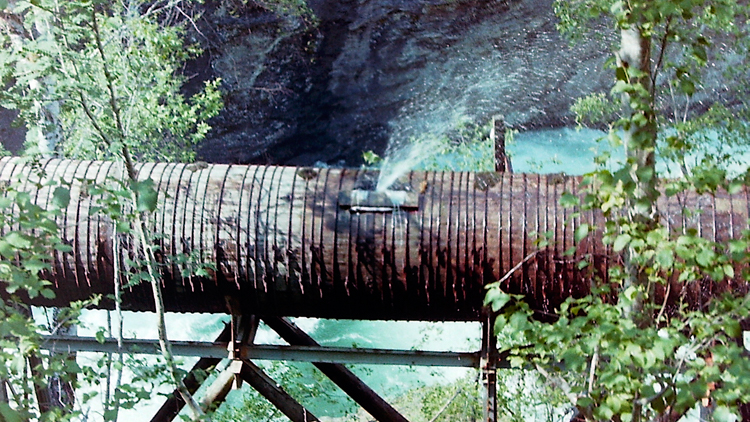

At the bottom of the gravel track, the Rallarvega becomes a formed road and winds along the valley floor. Occasional farms dot the landscape, but at all times the heart-breakingly sheer mountains tower above, punctuated by endless waterfalls. By each fall, some early settler has evidently built a house to take advantage not only of the water, but also of the view.

Emerging from a tunnel

John Martin painting (without the damnation)

Commuting from this Flåmbana train station would not be such a hardship

After almost 20 kilometres, we came abreast of Old Flåm, where we paused to admire the neat little church and its gravestones with their tale of a few families with familiar names (Flåm, Fretheim) spread over hundreds of years. Like the landscape, the social scene changes only slowly.

Arrival at old Flåm

Aegir Brewery

There is a brew pub in Flåm, but for most of our stay it had remained firmly closed. Over our stay I had managed to drink several of their products at different restaurants and hotels, particularly their stunning Imperial Stout. Norwegian alcohol prices are notoriously savage due to heavy taxation, but at NOK 185 (about GBP 18) for a bottle, I reckoned that this was probably the most expensive beer that I had ever drunk.

And then one day, the brewery doors were open, to reveal a bar modelled on a Viking longhouse, with carved wood and reindeer pelts and a large fire.

Bronwyn at the Aegir Brewery

After a few pints of the excellent stout, I got chatting to the brewer, Evan. It turned out that he had taken a batch of the stout that I was drinking, and then matured it in oak whisky barrels to make what he called ‘Lynchburg’. This was so good that, in an attempt to prevent it from being all drunk at once, he had almost doubled the price to NOK 340, or GBP 34 a bottle. This did not prevent a visiting American from buying the entire stock. Luckily for me, Evan had kept a case back for himself, and I was able to buy one, now definitely and without doubt the most expensive beer that I have ever drunk. It was worth every Krøne.

Happiness is a bottle of Lynchburg

Evan and Lynchburg Natt