Blackwater Rafting

We just happened to be on New Zealand North Island, where we had been Blackwater Rafting. This is a variation on Whitewater Rafting, and entails poking your bottom through an inflatable rubber ring, chucking yourself into a nearby river, and allowing it to swirl you underground down a dark hole.

Apart from being entertaining in itself, the main point is to see the glow-worms which make their home in the cavern roofs. The worms, encased in silken cocoons, emit a ghostly green light as they try to attract food in the form of newly hatched insects flying up from the water below. As you drift along in complete darkness, rubber ring bouncing harmlessly off the occasional rock, a stunningly beautiful constellation of green stars passes by overhead. It is weird, it is wonderful, and it is thoroughly to be recommended.

North Island to South Island by train

Auckland from the harbour

Once back out into the outside world, we towelled off and decided to climb the Franz Josef glacier. Not only was this on the other side of the country, it was on the other island and several days travel away. Nevertheless, from Auckland at the northern end of North Island it is possible to catch a train to Wellington on the southern tip.

Wellington cable car from the Botanical Gardens

From Wellington you can catch a ferry to Picton at the northern tip of South Island.

South Island looms across the Cook Strait

Salt flats on the way to Christchurch

From Picton you can take another train to Christchurch on the east coast, followed by yet another train (the Tranzalpine) clear across the country to Greymouth in the west, and finally a bus to Franz Josef. Since these trains between them comprise some of the most beautiful scenic railways in the southern hemisphere, we weren’t too upset about it.

Heading Westward

Further Westward

Ever Westward

Franz Josef

At lunch time, we stopped at a roadside cafe that sold Possum Pie (In Australia, possums are cute furry animals; in NZ, they are introduced vermin and have a nice rich flavour), we arrived in the little backpacker town of Franz Josef. With something of the air of a cheap ski town, it is a place to party, but not a place to dwell on the millions of tonnes of ice set to roll over the town if the climate changes.

After a celebratory beer or two, we dropped off to sleep in our slightly dodgy hotel, unsure of what the morrow might bring. In fact, the dawn light saw us trudging through light drizzle up the terminal moraine of the eponymous glacier. As we walked, our guides split the group of fifty into more manageable segments of ten; our own guide was a chatty little Kiwi called Imogen.

The long trek to the foot of the glacier

We crunched up the classic U-shaped valley, the footing strewn with the ground-up pebbles of millennia of ice erosion. Slowly we approached the enormous tongue of glacier towered above us, filling the valley from side to side, and high above we could see tiny ant figures perched on the face, chopping away with large axes.

The face of the Franz Josef glacier

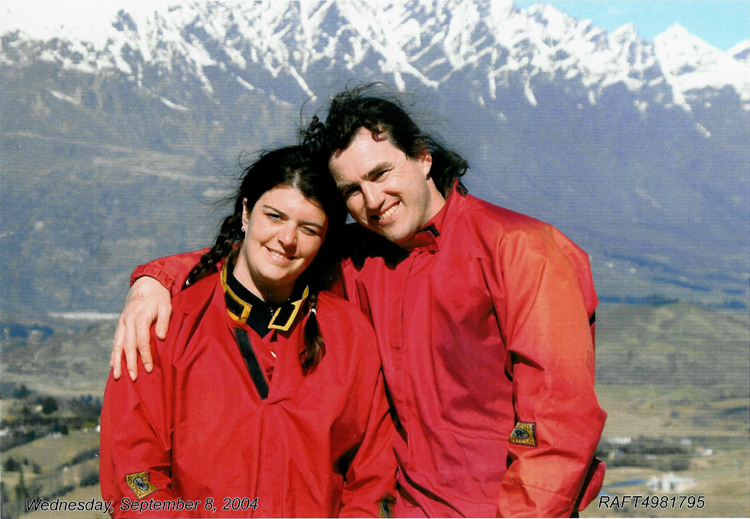

These people, we were told, had already been chipping for hours in the steady rain, making our path up to the surface. Every morning they make a stairway, and every night the glacier fills it in again. If you look very carefully at the picture of the face of the glacier (say about an inch from the bottom and an inch from the right), you can just about see one of these workers wearing a red jacket. Our group paused to put on our Ice Talonz, a kind of tourist crampon with a hinged centre that allows the leather boot of the wearer to flex more comfortably than with the professional climbing kind. Unfortunately, not just any leather boot will do; we had each been provided with a somewhat derelict pair of paratrooper boots, with gaping holes and ungainly repairs sewn up with string.

Ice Talonz (TM)

As somebody who had previous ice experience, I volunteered to be tail-end-Charlie for our group, and we set off up the icy stairway. We soon realised that the state of the boots was irrelevent; the Talonz were great. Halfway up, we were introduced to our ice axes, and then, as the rain stopped and the sun came out, we set off to explore our ice wonderland.

Imogen breaks the trail

Guides working on the face

The going wasn’t especially hard for us, but the guides were certainly working up a sweat.They carried large double-ended picks with which they were continually swinging and chipping, grooming each ice-cut step to a standard that would – just – allow ten sets of Talonz to pass before it was completely destroyed. Behind me, bringing up the rear, the leader of the next group began the same laborious process for the ten people behind him. In this manner, all the groups slowly worked their way up the face of the glacier.

Up the icy staircase

Once at the top of the initial ice cliff, the groups split up, each guide picking (and chipping) a different path onto the glacier proper. There certainly were a lot of routes to choose from. The surface of the glacier was crisscrossed with crevasses, sculpted ice peaks, ice walls, and ice caverns, with here and there a plank bridge to provide access to the next segment.

Bronwyn tip-toes over a snow bridge

It would have been very, very easy to get lost, because at eye level you could only see a few metres before the next turn or junction; certainly the other groups quickly disappeared from view as we set off down our chosen cleft. The only sign of them was the distant chip-chip-chip of the ice axes, and the occasional flurry of static from the guides hand-held radios, as they checked in with each other and tried to ensure that groups did not meet in any narrow gully or halfway along some steep ice shelf.

Up to the next level

At around lunchtime, we finished climbing to what seemed to be the summit, only to find ourselves on a pile of median moraine with views of the next few miles of glacier, an even more complex and tumbled labyrinth, dotted here and there with the occasional glimpse of one of the other parties as they wound their way in and out of the sculpted tunnels.

Glacier blue

After lunch there was time for a quick foray into the tumbled masses above us, then we got stuck in to the long trek back down. And a long trek it was! As the five day groups and the several half-day groups converged on the only ice stair at the tongue, the narrow crevasses got very congested. The guides continually radioed back and forth, and even though most of the time we couldn’t see further than a few metres, it was clear that all the other groups were very close by. Occasionally two groups would meet, and would have to work out some kind of precedence.

Even though the stair-dressers had clearly been chipping all day, once we got there the ice was melting with a vengeance under the combined onslaught of a day’s sunshine and a glacier-full of tourists. The stairway was a cascading waterfall. Standing in running ice-water and waiting for Imogen to chop away yet another piece of rotten ice, cold seeping through our soaking woollen socks, we began to wish that the guides weren’t taking quite such good care of us and would let us take our chances; anything to take a few warming steps.

Down the final stairway

Of course, they were doing the right thing, especially once we started to see some of the frail and unfit people who had just come up for an evening stroll; some couldn’t manage to step from one rock to another (we wondered how they would ever cope over the snow bridges), and one guy was clumping across the fractured ice in Talonz with a video camera glued to his eye; absolutely crazy, as we were all clinging with both hands and full concentration to any available handhold.

Safe and sound at the bottom, we removed our Talonz and headed for warmth and beer. Of all the adventure trips that we have done in New Zealand, this is the one that really deserves the name. We were climbing in quite dangerous terrain, and the guides had to be – and were – very, very professional; no larking about here. Imogen told us that to have Franz Josef on her adventure-guiding CV was the most respected experience that she could have. We were not at all surprised.