After a week of relaxing on Mala Island, we eventually had to rejoin the real world. Early one morning we boarded the little boat and chugged across to meet Dave the driver in his taxi, who took us back through the dawn light to the airport on Niufea.

We presented our pre-booked, pre-confirmed tickets to check-in, where they told us that we could not fly because we were not on the manifest. This was our first introduction to Tongan politics. The King, a generally benevolent and much-loved character, actually spends a lot of his time in hospital in the US, leaving the control of his realm to the Crown Prince, who we heard was a bit of a playboy.

The story goes that whenever a Tongan business is successful, the Crown Prince appropriates it, and it seemed that this is what had happened to our airline. Apparently he needed our seats for some friends of his, and that was just the way it was. We weren’t flying anywhere.

Niufea

Niufea is hardly a metropolis, but we found a nice cafe, and while Bronwyn tried to get onto the internet (four PCs sharing a single dial-up modem), I went in search of the post office. The building, when I found it, was reminiscent of a prison in a spaghetti western. The public was separated from the staff by floor-to-ceiling iron bars, threaded amongst which were dozens of letters which had been addressed “post restante”.

I bought some postcards and stamps to while away the time. Since the post office didn’t have any coins, they gave me my change in still more stamps, and I took the resultant pile of paperwork back to the cafe, where I managed to get hold of a bottle of the elusive Royal Tongan Ikale beer. It’s elusive because most quality establishments refuse to stock it, gleefully quoting stories of all sorts of foreign objects found in bottles since the takeover of the brewery by the Crown Prince. Certainly, I must have got an old, pre-Prince bottle, because it was tasty and refreshing.

Tongatapu

The next day we were first in line at the check-in, and actually got a seat on the plane for an uneventful ride to the capital, Tongatapu. On arrival, we stopped at a cafe for another (perfectly fine) bottle of Ikale, and then headed in the increasingly oppressive heat for the Dateline Hotel, supposedly the quality hotel of the islands, and advertising itself as “The First Bar That Opens in the World, Every Day”. We figured that they might have air conditioning, and since we’d only recently drunk in “The Last Bar to be Open in the World, Every Day” across the dateline in Samoa, it seemed like the reasonable thing to do.

We were greeted by a uniformed bellhop and escorted to a table, which was promising, but noticed that the place looked a little run down. It was with little surprise, then, that we discovered that this establishment, too, was now owned by the Crown Prince. We ordered Ikale, and it must have come straight from the new-style brewery, because it was completely undrinkable. I took a couple of sips, and then felt a compelling urge to go to the toilet. I scuttled in the indicated direction, and entered a marble-tiled, gold-tapped facility that hadn’t been cleaned for months. The first cubicle that I opened (and by this time I would have accepted pretty much anything) was… well… you’ve seen ‘Trainspotting’, right? But I used it anyway.

Back in the bar, Bronwyn had opted for the more sensible water option. Even then, the proffered glass bore enough grease to fry an English breakfast, so we gave up headed back out into the heat.

This was not the last surprise that the Crown Prince had in store for us. Bronwyn had used my mobile to leave a five-second message on her sister’s Canadian answering machine. A month later, when I received my mobile bill, I found that those few words had cost us just under sixty Australian dollars. The mind boggles at what the charge might have been if Michelle hadn’t been away from home that day.

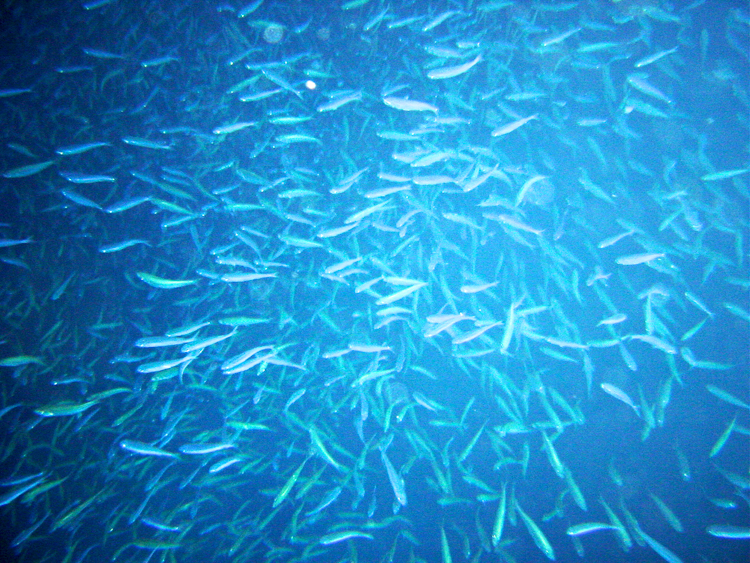

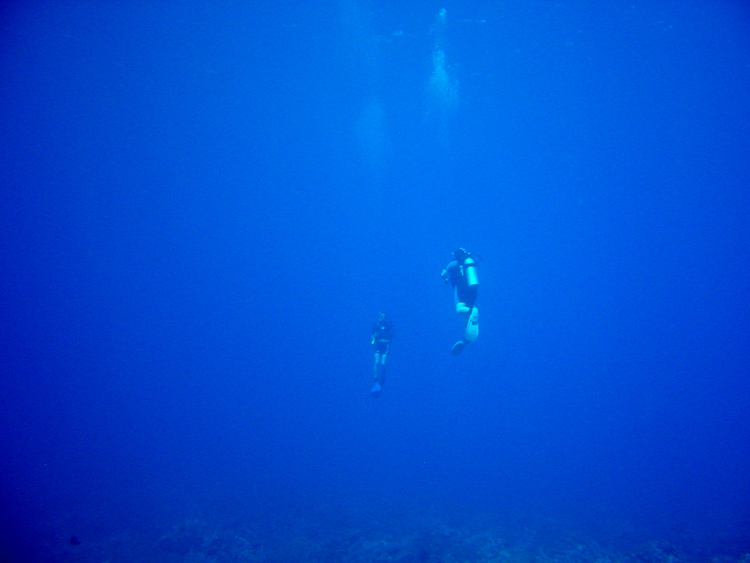

Our final Tongan legacy cannot, however, be laid at the feet of the Royal Family. Somehow or other I had scratched my elbow, perhaps on coral while diving, and the resultant sore was very slow to heal. As we subsequently travelled from country to country it didn’t seem to be getting any better; in fact, if anything, the wound seemed to be getting deeper and wider. After a week or so of this, a doctor in Brussels had a poke around and pronounced that I had a staph infection. “Is that bad?” I asked. “Well,” she said, “if these antibiotics don’t work, then you will lose your arm…”