Pindimara is a Bavaria 34, a standard European production boat, and her electrical systems were clearly designed to be plugged into shore power for most of the time. She has a huge and effective shore-power charger with 240 volt AC takeoff to run any convenient household appliances that you might care to carry on board, but if you’re cruising (or indeed living on a mooring), then your only recourse is to run the engine, which powers a standard car alternator and regulator, which really is not capable of giving a house battery a decent charge, especially with the saloon lavishly kitted out with power-hungry halogen spotlights.

Fridge

The fridge has completely laughable insulation. It is possible that it might keep the beer cold in northern Europe, but it has no chance at all of coping with either Australian or Pacific conditions. The normal expected insulation thickness for an electric fridge is three inches or more; this one has barely one inch and spent most of its time either sucking power out of our batteries, or shutting down because the voltage has dropped too low.

We had researched adding extra insulation to the existing fridge, and ripping it out and fitting another one, but in the end we bought a portable Engel 40 litre fridge, which is designed to sit on the back of a ute in the outback and to run for only an hour or so every day if left unopened. It can even run as a freezer if you turn up the power.

We’d tested it out for some time on land and, suitably awed (the Engel is a legend in Australia) had moved it aboard to see what it did to the batteries. The food stayed frozen, but we sill had to run the engine at least once a week to recharge them and we weren’t even living aboard yet. We were clearly going to have to upgrade the house system.

Solar Panels

After in-depth research we concluded that what we really needed was a pair of a kind of solar panel known as the Unisolar US42. These were marine grade, reputedly indestructible, the right power rating, and were shade tolerant so that they wouldn’t mind too much that our backstay was running up between them. In addition they were the only panels on the market which exactly fitted onto our shiny new stainless targa frame without any overlap. There seemed to be plenty of them around in chandlers’ catalogues, so we put in an order for them, only to find that they were out of stock. We ordered them from another dealer, who kept us hanging on for weeks before finally admitted that they were on back-order. A third supplier admitted that even though they had them listed in their catalogue and they were one of UniSolar’s most popular lines, they were in fact no longer being made, having been been discontinued in favour of the larger US64. Naturally, the US64 was far too big to fit on our targa.

Bronwyn the e-bay queen went hunting. Eventually she tracked down one display model that had had some rewiring done to it, plus a dusty old one in the back of somebody’s warehouse, and… not one other in, as far as we could tell, the whole wide world. Luckily she was able to secure both of them, and in due course they showed up in torn and tattered packaging. I fired them up one sunny day to check, and they both seemed fine, so I was eager to plumb them into the boats systems.

I knew from my reading that our problems with dim yellow lights and warm fridges were only to be expected, because the car-style alternator and regulator on our Volvo Penta, although perfectly capable of keeping the cranking battery in reasonable condition, is utterly unsuited to the task of properly charging two large deep-cycle house batteries. Standard regulators are only capable of charging a deep-cycle battery to about 80%, which is really only just shy of usefully flat. What we needed was a smart charger, a piece of electronics which continually monitors the batteries and keeps them on trickle charge until they are 100% full, along with some type of long-term power generator to charge them if we didn’t want to keep running the engine and using up precious fuel.

Our solar panels were intended to fit the bill, supplemented by a wind generator at night. Now I had to buy that smart charger. In the end I chose one from Ampair, because they also made my chosen wind generator and because it was one of the few on the market that would simultaneously charge from two sources. It proved enormously difficult to obtain. Not, this time, because they were out of production, but because all the dealers kept sending the wrong, single-input model. I ended up with quite a pile of single-input smart chargers from dealers all over the world before I finally got the one that I wanted.

We were, of course, now in proud possession of a serious stainless steel targa frame over the helm. All we needed was a little piece of canvas to strap to the top to protect us from the sun and rain, and then we could bolt on the solar panels, generators, aerials, and all those other bits and pieces that make a cruising yacht look like a travelling junk yard. We were living in Sydney, with marinas and slipways and workmen all around, so how hard could it be to arrange a bit of marine canvas?

It was, of course, a nightmare. Most of the telephone numbers that we tried either didn’t pick up, or didn’t return our calls. Those that did pick up, couldn’t fit us in this year, or perhaps any year. Eventually, by dint of haranguing all our nautical friends and neighbours, we did get the number for Shane, who seemed to be the best (or at least, the most reliable) in the business in our locality. Eventually we managed to connect with him, and booked a slot some months ahead. Those months soon flowed by, and he was apparently always too busy with this or that job to attend to us, but it gave me the opportunity to spent quite a bit of time at Aquavolt, an excellent shop where the incomparable Kurt answered every question, solved every problem, and unfailingly sold me the highest-spec equipment that money could buy.

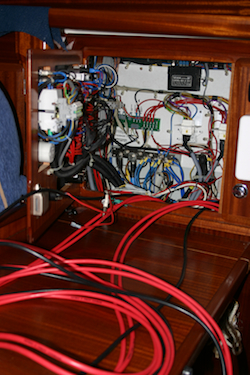

I was deeply concerned about power wastage, and was unhappy to follow the industry standard of a 5% transmission loss. That’s almost 5 of our precious peak power 84 amps thrown away in heating the wires, so I doubled the wire diameter and got the loss down to a theoretical zero. I spent a very windy day lying on top of the fuel tank in the lazarette with a gas-powered soldering iron, running my extraordinarily expensive cables through the bilges and wiring them up to through-hulls. I discovered crawlspaces and cutouts that I never knew we had, and finally patched everything together all the way from the transom to our snazzy smart charger; but still there was no sign of any canvas.

We were by now pestering Shane every few days, and one day when we rowed out to the mooring we were delighted to see that Pindimara was sporting a beautiful new canvas roof over the helm, with both US42s mounted sturdily above. I’m a bit picky about the way that I like my electrics to be wired, so we had agreed with Shane that he was to mount the panels but not to wire them in. I got out my tools and climbed up the targa to connect my wiring harness to the panels… and discovered that they had been mounted in such a way that it was impossible to get at the connections. Shane had provided us with some bits of wire hanging down, but they weren’t long enough to reach anywhere useful and anyway I wanted to wire the panels in parallel.

There followed several days of increasingly frustrating emails and phone calls as I tried to get Shane to tell me the best way of dismounting the securely mounted panels with minimum disruption, while he for some reason stubbornly refused to help. He didn’t seem to think that it was at all odd to leave the panels in an unusable state. Eventually, however, he did give me the information that I needed, and I partially unlaced the canvas and, with the help of Bronwyn’s small hands, managed to finish off the wiring.

I removed the roped-on cardboard shields, and waited in some trepidation as the first rays of sun hit the solar cells. I was suitably impressed. My jury-rigged ammeter twitched and then swept across the dial; each of our panels was generating slightly more than its published rating. Over the next few days we marvelled at how, in conjunction with our smart charger, those two panels kept our batteries topped up and conditioned even with both fridges running. We had solar power!

We discussed ripping out the old Frigiboat fridge and mounting the Engel in its place, but neither of us is excited by woodwork and it seemed like a lot of fuss. In the end, we removed the mattresses from the back cabin and mounted the Engel in there, on a sliding rack so that most of the time it was hidden away on the centre line. This also gave me the opportunity to turn the back cabin into my chandlery/workshop, so I moved in all my tools, spare parts, bits of string, sail bags, and half-completed projects. Suddenly there was a lot more room in the boat’s lockers, and we turned the original fridge into a wine cellar.

Wind Generator

Flushed with success, I unlimbered our Ampair 100 generator, which had up to now been sitting in a box in storage. It’s quite a clever piece of kit, comprising a cast-iron generator body that you can either mount with a windmill blade and hoist in the rigging, or hang from the stern with a propeller on a line which you tow along behind you. Either way, it was supposed to generate oodles of power, and we’d had it shipped from the UK to America to Australia to take advantage of the exchange rates and free trade agreements. It was pretty clear that we were going to need some more stainless work to mount it in tow mode, and I really wasn’t in the mood to deal with any more local fabricators, so I hoisted it up on the foredeck on the spinnaker halyard and started to bolt on the windmill fan.

It wouldn’t fit. I disassembled the fan, and reassembled it backwards, but it still wouldn’t fit. I tried it this way and that, and then got a second opinion, but Bronwyn couldn’t get it to bolt on either. There were two screw holes and two bolts, but they just wouldn’t line up whatever we did. A frustrated email to England resulted in a speedy and glad reply from the manufacturers. “Aha!” they said, “We’ve been looking for that faulty propeller boss.” Apparently they’d had a bad batch from the factory, and knew one had been sent out, but not to whom. They agreed to send a new one, as well as a small box of spare cruising parts as recompense. When the boss arrived, it fit perfectly first time, so I plugged in the generator and hoisted into the fore-triangle. Naturally, we didn’t get any wind all week.

Then, finally, at the beginning of the weekend, a southerly storm came in and it really began to blow. We watched in delight as our ammeter climbed to 5 amps, and couldn’t resist snatching the occasional look through the forward hatch to make sure that it was still spinning. It was remarkably quiet; almost silent, in fact, over the sound of the wind, and didn’t bother us at all even though it was mounted only a couple of metres above our forepeak cabin. Then, a few hours into the night, the storm really started to fire up, and I was awoken by the tortured howl of a turbine generator. I leaped out of bed and ran up on deck, only to be confronted by the Ampair blurring calmly and silently in the moonlight; all the noise was coming from a generator on another boat some thirty metres away.

Batteries

I’d taken the opportunity to replace our six-year old 180 AmpHour deep cycle batteries with some smaller, more modern ones, and it turned out that I could fit three 225 AmpHour Trojans into the same physical space. With the new batteries, the solar panels by day, and the wind generator by day and by night, we found ourselves for the first time having the luxury of almost unlimited electrical power without ever running the engine. Not only did we have constant and reliable refrigeration, but we no longer found ourselves having to go to bed because the lights were dimming. I shelved all my plans to replace our cabins halogen lights with low-consumption LEDs, which was something of a relief because our experiments had shown us that the technology was not yet really mature. The ones that I’d fitted were uncomfortably white and although they were bright enough directly underneath, their cone of action was annoyingly narrow.

Living aboard again

While all this had been going on, we had moved permanently on board, reckoning that this would be the best way of making sure that the boat was properly prepared for the upcoming voyage. We moved most of our stuff into storage, and a lot of it on board… and much of it off again… and then quite a bit back on… continually tuning and adjusting until we had everything the way that we wanted it. We were pleasantly surprised by how much room there was to store everything, although we did notice that the waterline was now two inches lower than when we’d bought her.