We sailed, and sailed. We sailed in heavy winds, and practiced reefing, both together and single-handed. We sailed in light winds, and tried our light genoa. We went out into swell, and practiced hoisting and lowering sails on a heaving deck. We stayed out overnight and practiced anchoring.

We booked marina berths, and practiced entering them both forwards and backwards, in wind and in current. We stayed overnight in berths, and practiced setting mooring lines and springers. We practiced picking up a mooring under sail, heaving to, and crash-stops. We practiced using the autopilot, and steering to the wind, and steering to a pre-set course. We even tried steering with the emergency tiller, which really wasn’t a lot of fun.

A Touch of Wind

One morning, after a pleasant night at anchor, a big storm started to brew. It took us a few hours to sail out of the secluded creek where wed been staying and into the main body of the river, by which time it was gusting an exciting thirty knots or so. We put in a couple of reefs and headed down the Hawkesbury river for home. The wind got steadily stronger, until we reached the point where we thought that it would be prudent to bring the sails down altogether, and motor. The main dropped down just fine, but the foresail roller furler jammed with about a metre of sail still sticking out. It didn’t look much, but boy! did it have an effect as the winds got up to 35 knots. We were heading into wind, and the steering was all over the place as intermittent gusts grabbed the sail one way or the other, but there was no way that I was going forward as it was flogging dangerously and we had no tethers. The fight was hard, and we soon got tired. We were still a couple of hours from home, so we nipped into aptly named Refuge Bay to pick up a mooring and see if we could sort it out.

The first mooring that we picked – which was, necessarily due to our lack of precision steering, in the open far from shore – was a disaster. We got attached alright, but that little square metre of sail just kept on powering us forward, dipping the bow under the water first to the left, and then to the right. I tied myself on to the thrashing deck, and by dint of some interesting ropework, gradually got the free end under control without being hit on the head very much at all, and built a sort of rope cage around it to stop it from thrashing so much. By this time, the waves around us had breaking white tops and we were being pelted with spray, so we decided to move to a more sheltered mooring before figuring out what was wrong with the furler.

Across the bay, close in to the shore, was a mooring that looked OK. Since we now had proper steering, we tucked in behind a sheltering rocky peninsula and celebrated with a bite of lunch while we watched the white-tops rage past. We now had time to peer up at the foresail and pull and poke at it, and we came to the conclusion that in the excitement of high-wind furling, the first few metres had probably folded over and furled backwards. This would mean that as the rest of the sail furled correctly over the top of it, the twisted portion would be pulled ever tighter until no amount of grinding on the winches would get the last part in.

The only way out was to deploy the headsail, and furl it back up again. The problem, of course, was that we had to do this downwind (you can”t realistically furl on a mooring, or upwind), and so in the interim we would be sailing shoreward with a fully powered headsail in 35 knots, with only one chance of getting it right, and banking on the hope that our analysis was correct and there wasnt something else fatally wrong with the furler…

We waited for a lull, then motored out into the breaking swell. I ran down to the bow, removed my jury-rigged fix, and ran back to the stern. The foresail deployed with an evil crack and then it was winch, winch, winch, all the while keeping an eagle-eye out for backwards folds, until the last blessed metre rolled safely around the stay. Superb. Better turn now, before we hit the rocks.

Out in the channel, the wind increased to 40 knots, and since we were approaching the headland leading to the open sea, the swell was increasing to suit. However, Pindimara felt safe and happy, and the motor had plenty of power in hand, so we ploughed on.

At the mouth of the Hawkesbury is an area of confused waters where the river meets not only the sea, but also the mouth of our home Pittwater arm, and the waters around Lion Island, which is a big slab of rock that reflects any swell back at a 45 degree angle. Its a bit of a maelstrom at the best of times, and there are some broaching rocks on the lee shore leading to Pittwater. However, we are familiar with the area and it holds no fear for us, so despite staying a safe distance from the shore, we were not too perturbed and could concentrate on rolling over the swell without getting the decks too wet.

We were quite surprised to find a small open metal boat motoring along in the trough of the swell, but you get fishermen everywhere and we turned away to give them some space. Suddenly they started waving and shouting; their engine had chosen that moment to give out and they were drifting onto the rocks. There were four people aboard, none with life jackets and, apparently, they had no oars.

The gusts were now hitting 50 knots. We circled around, wary of the rocky shore, and tried to throw them a line. It was incredibly difficult to stand on the heaving deck and throw a heavy, wet rope with any kind of accuracy, and I suddenly gained an immense appreciation for the people who do this for a living. A couple of attempts fell well within reach of their boat, but now it seemed that they didn’t have a boat-hook either; evidently I had to actually drop the rope inside their tiny little vessel.

All the while Bronwyn was fighting to avoid the rocky lee shore, and trying not to crush their little egshell with our five-tonne hull, which meant keeping at least one trough away from them. Over the radio, we could hear the coastguard rejecting calls from any boats in inland waters; all their efforts were concentrated on a series of dismasted yachts and men-overboard along the coastline. We weren’t going to get any help from them.

At one point I did manage to get the end of a double-length rope into their boat, but somehow while they were making fast a knot came adrift and they ended up with both ends of one of our mooring lines, while I was left standing with a loose end of a second one secured to our boat. We were just going round for another try when we spotted another small motor launch heading our way. We intercepted it and asked if they could help. They were much closer in size and weight to the stricken tinny and I thought that they should be able to get in close without danger, and that is what they did.

We hung around and escorted the pair as the new boat towed the old one out of danger, and then watched in stunned amazement as a fuel can was passed over and their engine sprang into life. The idiots had run out of fuel! Even worse, without any acknowledgement or backward glance, they then motored off towards shore, taking our mooring rope with them, and we never saw them again.

Ah well. At least it gave me something interesting to write in the ships log.

Many feet make heavy work

We had also been taking on board a lot of guests. We soon decided that although it is technically possible to sleep six on board (and day-sail with eight), a total of two couples aboard is really the maximum if you want to have a good time. As captain, we are responsible for all crew, however inexperienced, and we felt that responsibility keenly. After a weekend of entertaining, however enjoyable, we often felt as if we needed another weekend off in order to recover. And then we had the guests who insisted on “helping”, and others who just broke everything they touched… Thankfully, these were in the minority, and of course on most weekends we had a real ball even if we were completely knackered.

Parties at anchor were one thing; it wasnt until we started giving interested friends basic helming instruction and found ourselves quietly compensating for their mistakes that we realised just how far we had come since our first forays onto Lake Burley Griffin. It was also always a lovely moment to see somebody suddenly “get it” and become a completely natural helmsman.

A season of sailing, and a season of guests, all took their toll on our nice shiny boat. Inside and out she started to get a bit ragged around the edges, and we began to notice obvious scratches and stains in the fittings, and wear and tear in the equipment. It was time to call a halt to the festivities, and do some maintenance.

Up the mast

One of the items that had been broken right from the start was the close-hauled indicator, an instrument that tells you where the wind is coming from. In actual fact, that didn’t bother us greatly because it isn’t particularly useful in ordinary sailing. You can get the same information from the wind arrow on top of the mast, the telltales (our wedding ribbons!) flying from the stays, the state of the water, the wind on your face, and so on. The real purpose of the close-hauled indicator is to feed wind direction information to the autopilot. Our autopilot has two modes; one where you simply give it a compass heading and it chugs along in that direction (useful under motor), and the other which is supposed to emulate a self-steering windvane (a kind of extra sail and rudder which you find on proper cruising yachts). The idea is that you can set the sails, and then tell the autopilot to always maintain the same angle to the wind, thus giving you a break from steering.

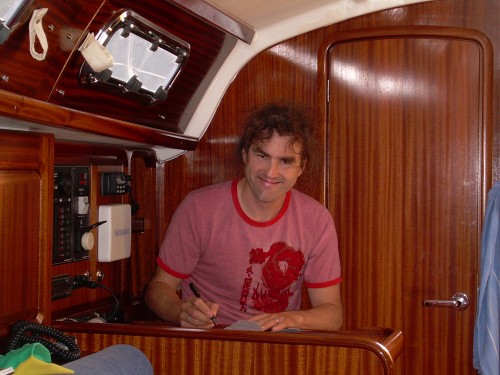

This still isn’t critical for anything, but its an expensive piece of broken equipment to carry around, and in any case, since the sensor is at the masthead, it gave me the perfect excuse to climb up the mast. There are a number of authentically nautical ways of going aloft, but I already owned a perfectly good climbing harness which I trusted to keep me safe while abseiling down waterfalls in the Blue Mountains If I was going to climb a fourteen-metre mast, then I wasnt going to mess about with unfamiliar techniques.

In actual fact, climbing is a bit of a misnomer. You wouldn’t want to put your dirty great feet on the expensive aluminium spreaders, and the mast itself is shiny and smooth without much in the way of finger-holds. No, what you do is assign a likely-looking crew member to the winches, attach the main halyard (and the topping lift as backup) to your harness, and lie back in luxury while she winches you to the top.

This is what Pindimara looks like from up there:

Buffing and Polishing

Our yacht is made of fibreglass. We had naiively assumed that this was a fairly indestructable material that would look good with nothing more than the odd hose-down now and again. However, in the marine environment, the gel coat discolours and even oxidises. Add to that the roughening impact of endless guests and their bags, and the deck and the inside of our cockpit began to look decidedly shabby.

I tried to buff the deck myself with a 12 volt sander and a sheep’s wool pad, but it was impossible to get a good finish. We engaged the services of our friendly local shipwright, and the weekend after a phone call telling us that she was as good as new, we popped out to the mooring expecting great things. Sadly, it was not to be. The yacht, which we had recently cleaned inside and out, was absolutely filthy and the cabins were full of dust. The deck was, if it were possible, even more matt than before, and the various old oil stains and bird droppings had apparently been ground into the deck with a power sander. The cockpit itself, which had been our main concern and the reason for getting the job done in the first place, had not been touched apart from to fill it with a layer of dried paste and some old rags. We were not amused. After some quite energetic discussions, the shipwright agreed to waive the bill, and we looked around for somebody else to do the job.

The general consensus among local people was a company called Reflections, who agreed to come aboard during the week and sort it out. After their phone call, I rode straight from work to the marina, got in the Zodiac, and rowed out to have a look, preparing myself for the worst. When I got to the boat, I almost didn’t dare set foot aboard. Somebody had apparently taken our yacht away and replaced it with a new one; it was an incredible transformation. In addition to spotless, shining decks, our teak flooring, which had always been a sort of beech grey, was suddenly a rich golden colour. I rowed straight back to shore, headed for their office, and willingly gave them a pile of cash. What an incredible job!

Sucking oil

Pindimara’s motor is a three-cylinder 29-horsepower Volvo Penta diesel engine. The service intervals are 100 hours, or once a year, whichever is soonest. We had now owned her for a year, and I had long been suspicious that precious little maintenance had been done thus far; not unless the previous mechanic had carefully repainted all the new filters in the original Volvo green colour.

In addition, I am always uncomfortable running an engine that I haven’t seen the inside of, so it was time to roll up my sleeves and get oily. Being more used to land-based engines, I had to learn some new tricks. Even changing the oil was interesting. Since the bottom of the block rests directly in the bilge, there is no room to get a tray underneath it. In fact, you cant even get a spanner to the drain plug. What you have to do is to buy a special pump and suck all the oil out from the top. I read various manuals and descriptions of how this process was supposed to work, and all clearly stated that the oil was sucked out of the dipstick tube. I managed to buy an oil pump (a nice shiny piece of engineering, made of brass) without any problems, but just could not fathom how I was supposed to push the sharp end down a tube that was almost completely inaccessible and shaped like yesterday’s share index. After much cursing, and to-ing and fro-ing with bits of brass and plastic tubing, I finally banged my hands painfully on a hitherto invisible pipe projecting from near the base of the block. Aha! A special, purpose-made oil pump tube. How convenient. From then on, it was just a case of pumping. And pumping. And pumping…

The Penta is water-cooled, by means of a seawater heat exchanger. All the various filters are easy enough to check and to clean, but the screws that held in the pump impeller had clearly never been moved, and one of them snapped right off, so that I was obliged to call in the local shipwrights for a bit of work with a drill and thread-cutter. The impeller is downright weird; it’s made of rubber and is designed to be far too big for the hole it turns in. The crankshaft obviously provides enough power to turn it, but it looks like a piece of old chewing gum when you finally cram it into place. As for the fuel filters… I broke two strap wrenches trying to get them off, and postponed it for another day.

Scrubbing the Bottom

It was by now some eight months or so since we had treated the underside with antifouling paint. During the process we had been forced to miss out on treating a transverse strip that had been occluded by the load-bearing strap at the yard, and I’d been keen to drop under and see how that patch was doing. For some weeks I had also been noticing a distinct sluggishness in the engine response, so one day at anchor in a small bay, I donned a wetsuit and went down to have a look. The strip of untreated hull was thickly overgrown, but I had expected this and had brought a stiff brush to scrub it off. However, there were other surprises in store.

First of all, I found a length of fishing line wrapped around the prop. This had been intercepted by our line-cutter which had almost cut it all away, so it wasn’t hard to pull out the melted remainder. The real surprise was the amount of marine growth over the propeller and the sail drive itself. You may recall that while we used expensive semi-professional paint for the major fibreglass portion of the hull, we had borrowed some cheap copper-free paint from a neighbour to do the few metal parts; the sail drive and the through-hull fittings. This was, it now turned out, a mistake. While the main bulk of the underside was perfectly fine and untouched by marine life of any kind, all the metal fittings, including the crucial seawater intake vents, were festooned with coral. An hour or two with a snorkel and brush soon sorted that out, and then it was time to quit working, and go sailing.