New Year: Pittwater to Swansea Bridge

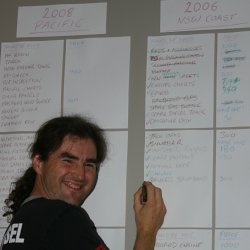

Apart from the occasional fair-weather foray outside of the heads, we had still yet to sail upon the open sea. The main reason for this was that we had decided not to go until we had an absolute minimum of quite expensive cruising safety equipment. I had made up a couple of wall-posters with lists of equipment and prices, and, crayon in hand, juggled them almost daily, rethinking and prioritising them within our monthly budget.

The last essential item on our list was a pair of jack stays. This became a real sticking-point. Jack stays are safety lines that run all the way along the deck from bow to stern. The idea is that whenever you leave the cockpit, you clip your safety harness to the stay and you then get freedom of movement while remaining attached to the boat. The jack stay obviously needs to be strong and well-made, since it is supposed to save your life if you get washed overboard. They’re not an off-the-shelf product, though; they need to be tailored to each individual boat.

Australia is, unfortunately and in line with many other western countries, becoming increasingly litigious, and we found it very hard to find any company that would make them up for us for fear of legal action if the stay should fail. The general consensus was a shaking of heads and tutting, and “we used to make them all the time, but….”

Eventually, however, we met up with a rigger who was prepared to take the risk. He made us a beautiful set which fitted perfectly, and we finally felt that we were ready to go cruising.

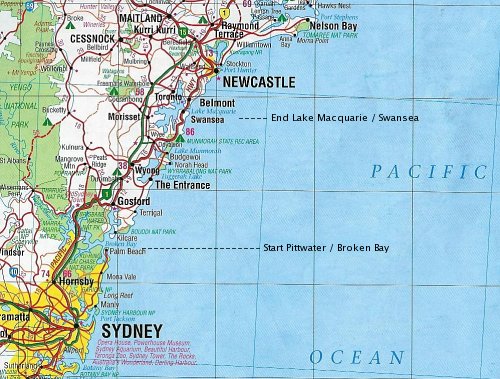

We had about a week encompassing Christmas and New Year. Theoretically, we could in this time sail all the way up the Australian coast from our home mooring in Pittwater, New South Wales, up to the next state, Queensland. However, we fully expected the weather to throw in a few spanners, and in any case we wanted to enjoy the scenery and see what there was to see, so we decided to head for the next available deep-water anchorage, Lake Macquarie, and take it from there.

The week started with rough weather, so we pottered around for a few days inside Pittwater, trying out some new anchorages and practicing single-handed sailing.

When the weather finally improved, and the forecast swells dropped below two metres, it caught us by surprise with only half a tank of fuel. We had intended to leave at dawn, but even though we anchored overnight outside the fuel station, we still had to wait for it to open in the morning, and so we didn’t actually clear the heads until ten. However, it was blowing around twenty knots and we figured that we should be able to make good speed. How refreshingly naiive we were! We had not factored in the fact that we were heading north-east into a nor’easterly wind, across a south-easterly swell.

A yacht cannot sail directly into wind; to travel upwind, it has to tack (zig-zag) from side to side. This substantially increases the distance that you need to travel in order to get from A to B. The swell was also a real pain. Usually swell follows the wind, so that you are travelling in more or less the same direction as the waves. On this particular day, the swell was crossing the path of the wind, making the waves steep and confused, so we spent a lot of our time climbing up waves and then falling off the top to crash into the trough, before the climb up out to the next one.

A cruising yacht accelerates only slowly; when your speed is continually being scrubbed off in every trough, its hard to build up any momentum, and as the boat wiggles over the waves it is hard to keep the sails at anything like the correct angle to the wind to provide motive power.

And finally, we were sailing close-hauled. A note here for the uninitiated about points of sail. If you are standing at the helm and the wind is coming from behind your shoulder (known as broad reach or running, depending on exactly where it is coming from), the hull sits flat on the water and the sails need little attention. It is possible to leave the wheel unattended for short periods and nothing bad will probably happen; more sensibly, you could turn on the autopilot and sit down and relax. Sailing with the wind coming from the front (close reach, close hauled) is more exciting; essentially you are flying a small aircraft sideways across the water, always threatening either to stall or to dive. The sails need constant trimming, the deck is heeled over at up to 30 degrees, and you are quite likely to get wet from spray and even broaching waves. In these conditions, the autopilot simply doesn’t respond fast enough and human control is essential.

All points of sail are equally valid and will get you to where you want to go. Some are just faster or more efficient than others. In a pottering-about or racing situation you just take whatever wind there is and deal with it. Cruising books, on the other hand, always talk about how important it is to make sure that the wind is behind you. Now we really understood why. When you’re just messing about in sheltered waters, you can always change direction and go somewhere else when it gets uncomfortable; in a racing situation, you only have to hold on until the next buoy. However, out to sea, you are travelling in the same direction for hours, days, weeks; the choice between fighting the wind and waves every minute of the time, and just relaxing and letting the autopilot sort it out, quickly becomes a no-brainer.

Nevertheless, we soldiered on. Our instruments were showing speed through the water of three knots. We were pretty sure that the instrument needed calibrating and was reading about a knot too low, but that still wasn’t fast enough to get to port before dark, so we turned on the engine for a little extra power. Purists will probably stare aghast, but it gave us an extra couple of knots and, in our book, safety is better than style.

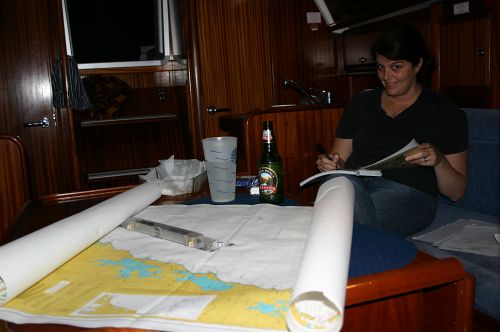

We had logged on with the coastguard when we left, and they were passing our paperwork up the coast from station to station. Periodically we called each station on the radio, and reported our best guess of what time we would reach the next one. Our guesses, based still on our original estimates, were pretty much on the nose, so we felt that we were doing something right. Of course, one of the important things about checking in with the coastal patrol is that you actually know where you are when you speak to them, so I had to periodically go below and see how the coastline (now several miles away) matched up with the chart. In this we were considerably helped by a book of photographs and charts published by Alan Lucas, a local sailor who has extensively surveyed this part of the coast. This made the task much easier than doing it from the official chart alone, but I still had to hang on to my seat while the boat pitched and crashed, trying to concentrate on little symbols on a big piece of paper that kept threatening to roll up.

Inevitably, I got seasick, but the jack stay allowed me to hang over the side with impunity, and the breaking seas quickly washed the transom clean.

Time passed. The seas got bigger and more confused. We passed one landmark after another, until at last we came in sight of Moon Island, which guards the entrance to Lake Macquarie.

The entrance to the river crosses a shallow sandy bar. As Australian bars go, it isn’t too bad, but it was still going to be touch and go with our two-metre draught. For the time of the tide, though, the charts showed that the bar should be open to us. The key was to line up with a row of port marker buoys which pointed the way to the dredged channel. However, on rounding the island, we found that the seas were so crossed-up and confused that we couldn’t see any buoys at all, just violent whitecaps.

Eventually, however, after bringing the sails down and slopping back and forth under power, we found the first of them, which led to the second, and to a clear shot at the bar. Lucas suggested hugging the port markers as we came through the breakwater, so that’s what I did, watching in bemusement as the depth-sounder dropped to only a metre of clear water under the keel. I waited for a break in the surf, and then gunned it through; the depth-sounder read 0.8, 0.6, 0.4, 0.2… and we gently tapped the bottom, once, twice. The numbers started to climb again: 0.2, 0.4, 0.6 metres. Clearly our depth gauge needed recalibrating to account for a 20cm error.

As we crossed between the breakwaters, dusk fell, and some previously unnoticed, bright blue lead markers lit up in front of us. They were not on our Admiralty chart and off to one side of our position; presumably the channel had been moved since Lucas had done his survey. We made a note to keep an eye on them on the way out. Meanwhile, we were through and in the channel.

It was still shallow and narrow, and it was hard to see the coloured channel markers because of all the christmas decorations on the shore, but we got round safely and picked up a visitor’s mooring in a few metres of water. Swansea Bridge was closed for the night, and wouldn’t be opening until the morning.

In the morning, the bridge opened, and we motored through.

Lake Macquarie

We weren’t in the lake yet, by any means; there is a long and winding channel over shifting sandbars from Swansea Bridge into Lake Macquarie proper which, combined with a fast-running tide, made for an interesting trip. Once through the channel, we found a pleasant, large, and above all shallow lake, well populated with services.

Over the next few days we tried out a few anchorages, watched the New Year’s fireworks, visited a few marinas, and generally relaxed. Our favourite place turned out to be the Lake Macquarie Yacht Club at Belmont, where we secured a berth for a week so that we could take the train home and go back to work.

Running Home

The following week, with the forecast showing nor’easters and very little in the way of swell, we rejoined Pindimara for the trip home.

In a light pre-dawn mist, with the rising sun shining directly into my eyes, I failed to see one of the channel markers. Since the channel zig-zags about to follow the shifting sands, the result was an impromptu off-road shortcut which saw the bulb keel firmly embedded in the bottom. With a strong current running, it all got a little exciting until I managed to turn her around and power back the way we’d come. Bronwyn has been below when we’d hit, and had taken a bit of a tumble, so I was relegated to coffee duty while she took over the helm. While still wagging her finger at me, Bronwyn then ran aground herself; this time we were exactly between the channel markers in precisely the right place. The tide was high: it was just too darn shallow, whatever it said on the chart.

After an interesting time trying to refuel (most of the fuel docks in Lake Macquarie are too shallow for us, and the one that is deep enough, runs with a 6-knot current), we anchored up close to the channel entrance and waited for morning.

The bridge opened for us, we followed the leads out across the bar, and we were back in the open sea.

What a difference it made going in the other direction! The deck was flat and the sails well-behaved, and we easily got up to four or five knots.

After some hours of breezing along, Bronwyn went below to sleep, and I tied off the boom and switched over to George the autopilot, who could easily cope with these conditions.

This was clearly the way to do it. We made a note never to beat into wind again.