It was time to spend some big bucks, and to get a stainless steel frame made for the stern. This would carry a sunshade for the helmsman, provide extra security around the cockpit, and serve as a mounting place for our solar and wind generators.

After getting a number of quotes, it was quite clear that getting work done in Sydney was far more expensive that getting it done further up the coast, so we decided to shift our base of operations up to Port Stephens, about seventy miles to the north east.

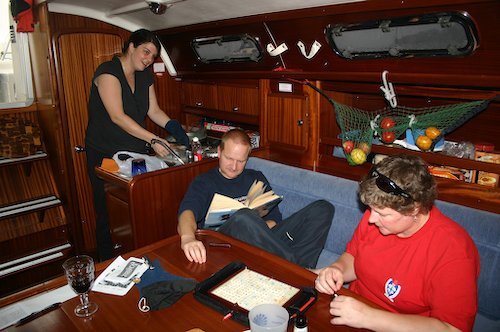

Chris and Nicky were keen to do some offshore sailing, so we invited them along for the trip.

After a quiet night on the mooring, we got up sometime before dawn, waved goodbye to Gibson Marina for the last time, and motored out to the heads. We had only been going for about half an hour when the engine overheat alarm went off. I quickly shut down and we drifted under the stars while I searched inside the engine bay for any sign of a problem. However, everything looked just fine, and the engine restarted with no problems at all, so I could only surmise that a plastic bag had temporarily wrapped itself around the cooling intake.

Dawn came as we cleared the headlands, bringing with it a light wind that spun gently around the compass for a couple of hours, before firming up into the promised 10 knot easterly, punctuated by 25 knot squalls that each merited a reef in the mainsail. We tried to reef the foresail, too, but it wasn’t terribly effective when partially furled so we just left it flying. Apart from the odd drop of rain and some mal-de-mer, it was a beautiful trip, very different from our previous attempt. We headed out on a broad reach until we reached a depth of 40 metres, passing lines of empty coal carriers queuing up to enter Newcastle.

In sight of Moon Islet we dropped the sails and motored across the bar. Last time we’d hit bottom, but on this occasion we followed the lead lights religiously and got through with 0.6m under the keel. Rather than go through the bridge and up into Lake Macquarie, we just hooked up to a courtesy buoy, as we were planning to leave early the next day. The engine hadn’t caused us any further grief. I had intended to dive down and have a look at the intakes, but there was a strong tidal rip and I didn’t want to risk it in the gathering dusk. We judged that the same currents were also too strong for our rapidly deteriorating Zodiac, so instead of rowing over to a nearby pub, Bronwyn knocked up a meal from things that she found in the lockers. As usual, it was excellent.

During the night there was a heavy squall, and the boat got caught up in the battle between the tide and the wind. I got up several times to try to prevent the courtesy buoy from banging on the hull, and on one occasion I noticed rainwater pouring in through the ceiling of our forecabin, running down the bulkhead and disappearing into the bilges. Finally, then, I had tracked down the source of all that mysterious fresh water that kept accumulating in the bow.

The tide finally turned at 01:00, and I dropped off into blissful sleep as the boat quietly settled down. Of course, I was up again at 04:00, motoring back down the channel in the dark. We cleared the bar, only to find that the horizon was lit end to end with the lights of dozens of bulk carriers, all anchored along the 50 metre line. It looked like an entire city out there. As we headed towards them, the sun came up to reveal patchy blue skies with flocks of little white cumulus marching out the south east, and small squalls mooching about beneath.

Our plan was to head out past the anchored ships to the 100 metre line and then aim straight across the enormous width of Stockton Bight toward Port Stephens, because the inshore waters had a bad reputation and in any case have never been adequately charted. However, just as we reached a depth of 40 metres, one of the squalls came our way, so we turned to run before it, and once it had passed we were right in amongst the ships.

This turned out to be an interesting detour. Most of the ships seemed to be, as far as we could tell, either Japanese or Korean, although most were registered in Panama. There was a lot of foreign language chatter on Channel 16, and many of them seemed to be undergoing repairs; at least, there was a lot of angle-grinding going on.

The wind came and went as we zigzagged between the enormous walls of rusty steel. The bottom readings were very strange; at one point the depth jumped from 48 metres to 4.1 in less than a second. I put the helm over hard, and we didn’t hit anything. Because of the flaky nature of the charting, we couldn’t tell if we’d encountered the mother of all sea mounts or an inquisitive great white shark, but Bronwyn quickly plotted us a direct-line course to Port Stephens, which was still over the horizon, and we got the hell out.

The weather turned beautiful, and we got up to our maximum speed of five knots. A pod of dolphins showed up to play in our bow wave, and surface-skimming petrels, groups of yellow-headed gannets, and long-necked divers congregated all around. Our charting proved to be on the nail when land appeared on the horizon, and we dropped sails to motor across the entrance of the bay, which turned out to be shallow but with no real bar. Willing hands took our mooring lines as we backed into an easy berth at The Anchorage, where we headed for the excellent Merretts restaurant for a well-earned restorative. We had arrived.

Antifouling

Our next task was to get her out of the water for her annual antifouling. Last year, we hauled her out with a cradle, which meant that there was quite a large area that remained unpainted because it was under the sling and we couldn’t get at it. This year, we went to the excellent Noakes Boatyard in Nelson Bay, who took her out with a crane and plunked her down on four little pads, so that we could get at almost the whole hull.

One thing that was patently obvious was that although last years expensive hull paint had done a fine job, the cheap stuff that wed used on the sail drive and propeller had definitely been a false economy. This time, we would use better stuff. We also needed to add an extra couple of inches to the waterline to account for all the extra stores she now carried aboard.

The nice guys at Noakes also gave her a thorough polishing and fixed some gashes in the fibre glass that were the legacy of a lee wind on an old wooden pontoon at Lake Macquarie, and, after some detective work with a high-pressure hose, we located and taped up the defect in the deck that was the source of our freshwater leak.

Sail Maintenance

We invited John Herrick, a local sailmaker, to come and check our sails. He professed them baggy but repairable, and also agreed to add a third reefing point, as well as to make us a new small, strong cruising genoa and a storm trysail. Later on, as we let down the mainsail, we discovered (courtesy of a bloody finger for Bronwyn) that all the battens were fractured, as well as a few of the sliders; maintenance was well overdue.

I loaded both sails onto the back of the motorbike, and then contrived a tube so that I could also take the 3 metre battens, stayed with guy wires to stop them whipping around too badly. It was an interesting ride into town, avoiding overhanging trees, and, in downtown Nelson Bay, a 3 metre clearance footbridge which meant that I had to slalom the bike to get safely through. However, I got to Johns workshop without any problems, and left them with him while we rode back to Sydney.

Interlude

Then came the cyclone, which destroyed a whole marina in Lake Macquarie, damaged yachts up and down the seaboard, and even tore up one of the bulk carriers and drove her onto the beach at Newcastle. The roads were closed to traffic due to flooding, so we couldn’t even get up there to check if Pindimara was OK, and it was several nervous weeks later before we saw her again.

Bouncing around on her mooring, she had scraped some of the antifouling off near the bow, but apart from that she had sustained no damage at all, and as a bonus there wasn’t a drop of water in the forward bilge.

The poor old Zodiac, however, which was our sole method of access to our boat, was getting more and more battered with every use. The supposedly indestructible, lifetime guarantee rowlocks broke again, so I threw them away and poked the oars through the carry straps instead. This made everything a bit slower and less efficient, but at least I didn’t keep falling backwards when the rowlocks snapped or jumped out. Then the spring lock broke on one of the paddle blades. I taped it back on, but then the floor came away so that I had to row with gallons of water aboard. The whole thing was by now in such a bad state that I was just leaving it rolled up behind the bins, trusting that nobody would bother to steal it.

It was definitely time to buy a new tender, but we couldn’t really afford it, and even if we’d bought one, there was nowhere at The Anchorage to store it. We decided to move to a marina that provided a free taxi service. Soldiers Point Marina had a spare mooring, and a little metal speedboat that they used as a tender. They were also the home base of Bluewater Stainless, who we had chosen to do our steelwork. It seemed like an ideal choice, so we said goodbye to the fine people (and fine dining!) at The Anchorage, and set off around the bay.

On the way, we picked up our refurbished sails. What an incredible difference! As well as repairing and strengthening the seams and replacing the battens, John had taken out all the bagginess in the sails, restoring the balance of the boat to as new. We had been fighting the weather helm for so long that we’d forgotten that it used to be any different; now we could sail close-hauled with but a single finger on the wheel. Pindimara was reborn.

Soldiers Point

Once installed on a swing mooring at Soldiers Point Marina, we had to wait for the guys at Bluewater Stainless to fit us in to their schedule. The weather was conspiring against any marina work, so they were concentrating on other projects. The months wore on. One weekend, I rode up from Sydney to check that she was OK and to do some minor maintenance. I hopped into the marina’s tender for the quick trip over to the boat, and sat back and chatted about the weather as we motored out to the swing moorings. The tender lacked fenders, being a simple aluminium dinghy with a steel scaffold pole welded around the bow, but this didn’t matter much because Pindimara’s sugar scoop stern entry is protected by a full-width rubber bumper. There was a bit of chop, so the helmsman announced that he was going to tuck under the side rather than head straight for the stern. I often do this myself. When the yacht is streaming off a buoy, it can be worthwhile to come up in the lee of our big fat beam and hand-over-hand around the corner to the stern entry, rather than try to crab sideways into the wind and current for a direct approach.

We were powering up to the port side, and as I waited for the turn alongside so that I could catch hold, I admired the fantastic job that Noakes had done with buffing and polishing the fibre glass. Pindimara looked like a million dollars. At the last second, the helm said something like “Can you fend off?” and then t-boned her amidships. I had reflexively jumped onto the bow and did get one hand to the toe rail, but I was pushing against the thrust of the outboard motor and all that I really achieved was to get a grandstand view as the scaffold pipe punched a hole straight through the fibre glass with an awful crunch. We bounced and hit twice more until the helm finally got the outboard into neutral, leaving me staring in disbelief at the palm-sized hole and long black streaks down our pristine hull.

I was not best pleased. The pole had gone in across the junction of our blue and white gel coats, meaning that two separate repairs were required on the same hole, one for each colour. Incredibly, the marina were very slow to admit responsibility, and it took a lot of arguing before they finally agreed to get it repaired. Then they said that for insurance reasons they would have to withdraw the tender service to our boat, which left me with a bad taste and us stranded without transport again. Nevertheless, we didn’t want to leave for another marina until the fibre glass had been repaired, and in any case we didn’t want to miss out if Bluewater suddenly got a chance to do our steelwork.

I unrolled the Zodiac again from its resting place on the hatch cover. Although the main structure was failing fast, at least my puncture repairs had held up for all this time. I reckoned that it could survive a few more trips, and, once back on shore, I tucked it rolled up under a pile of scrap in the shipyard. Hopefully we would be gone in a couple of weeks.

Another month passed without any action. Then, finally, our yacht was moved into the work berth, and Bluewater made a start. They disassembled our safety lines and stern rails, and made some progress making up frames in their workshop. However, the weather was not cooperating with actually fitting the steelwork to the hull. Because of the configuration of their berth, they had to ensure that they were not welding in a westerly, because that would blow the sparks onto craft in the surrounding marina. Naturally enough, we had weeks and weeks of alternating westerlies, storms, and rain. More weeks passed, with no progress that we could see apart from some holes in the stern that precluded any sailing, and the four-hour commute at weekends to sit on a stationary, half-disassembled boat started to get a bit tiring. At last, some six months after we first arrived, the weather started to cooperate and it all came together. The hull was patched up, and our new stainless went on.

Rather than just build and fit our targa top, the guys at Bluewater had pulled out all the stops and provided us with complete solid side rails all the way along the cockpit, and even some gates on either side. It looked absolutely spectacular.

It was at about this time that we began to get suspicious about the amounts that the marina were debiting from our credit card for our mooring. The numbers didn’t match up with what we had originally been quoted, and, after an uphill struggle to obtain a copy of the invoices, we found they had also charged both us and Bluewater for the time that we’d spent on the work berth. It was pretty clear to us that this was their way of raking back the costs of our hull repairs. We had intended to use a third local company to make the canvas for our targa, but when we found that they wouldn’t be able to start work for another six weeks, we decided that it was time to leave for friendlier waters.