We left on the dawn tide.

Of course that’s complete rubbish. What we actually did was have a leisurely breakfast before motoring gently out of the creek some time during the mid morning. But we did make very sure that the tide was still rising, because the Great Sandy Strait is far too shallow for us to navigate otherwise.

Large sea turtles poked their heads out to watch us go. They were very nervous, only popping their noses up long enough for a quick snort of air; by the time you’d turned your head to see them, they had gone, leaving only a spreading circular ripple. Some of the heads didn’t look quite the same, and we realised after a while that some of them were dugongs rather than turtles.

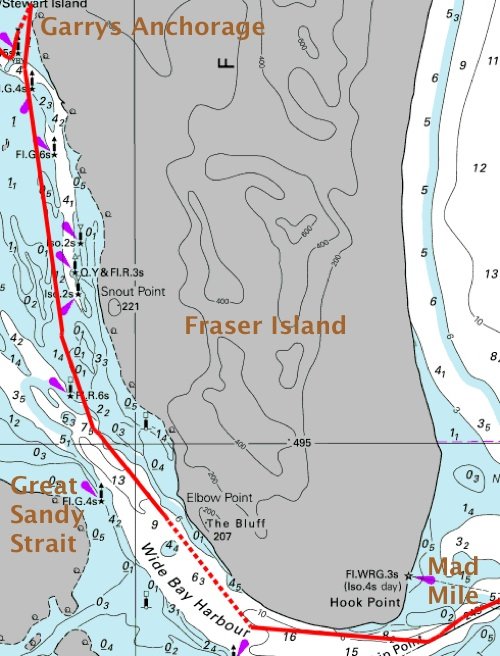

There wasn’t any wind, but we were happy to motor along in the sunshine, navigating from channel marker to channel marker. There were plenty of markers, but there were also plenty of sand banks and channels, and often it wasn’t exactly clear whether the marker that you could see was in your channel or in an adjacent one. I wouldn’t have liked to do it in the dark, or even on a cloudy day.

We only had a few hours to get through the really shallow portion of the Strait, but the 2.4 metre high tide carried us through with little cause for alarm. We did pass over a few places where we had less than a metre under the keel, confirming that we would never have gotten through at low tide.

When we reached the North White Cliffs which mark the end of the shallow portion of the passage, we plonked down our anchor for a few days of relaxation.

The beach is only a few tens of metres away, consisting of sand eroded from the overhanging cliffs overlying some exposed coal measures.

From here it is but a gentle stroll to the Mackenzie Jetty where steam trains used to haul milled timber out to waiting barges. The mill and the associated houses have all gone, but most of the jetty still stands and there’s some abandoned hardware on the beach, including an old locomotive boiler.

A little inland is the site of the wartime headquarters of Australia’s secret Z Squadron, from where they launched training limpet-mine missions against presumably good-humoured local boats and businesses, and real and very dangerous missions into Asia and the Pacific. Most of the base has rusted away, but the history and photographs were interesting. I was bemused to see that the old tyres from their abandoned vehicles are still practically useable after over fifty years of lying in the bush. No wonder tyres aren’t welcome in landfill sites.

We’re also on the edge of Kingfisher Bay where there is a small resort. We had formed high hopes of sundowner cocktails at the beach bar, but it turned out to be just a standard schnitzel-and-cheap-lager joint, so we gave it a miss. The resort itself seemed pleasant enough, but had an aura of neurosis about it, being completely surrounded by a tall dingo fence behung with pictures of slavering hounds and dire warnings about letting children play unattended. We were exhorted to “attack vigorously” if approached by angry dogs. Instead, we had a champagne picnic.