We had embarked on a four-day passage up through the Great Barrier Reef and out into the Torres Strait. The trade winds were blowing fairly consistently and the weather forecast was good. It was also stinking hot, and we discovered that some of our eggs had cooked themselves inside their shells.

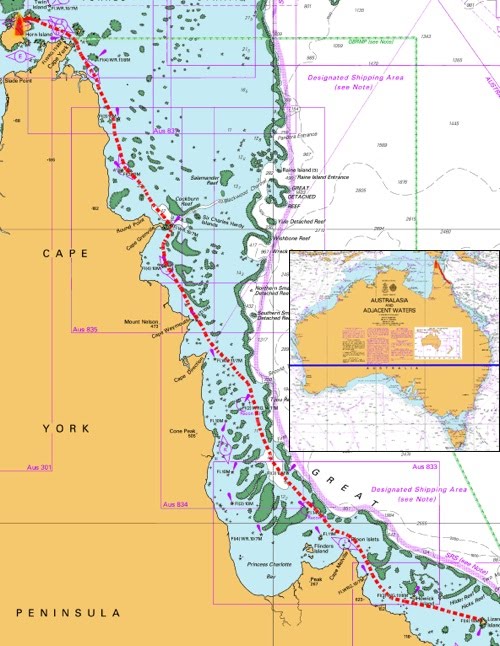

The Great Barrier Reef is much more than the outer ribbon reef that protects the eastern coastline from the open ocean. Inside the enclosed lagoon are tens of thousands of square miles of shallow water dotted by uncountable reefs and islands, many of them still uncharted. The reefs are mostly invisible and lurk just below the surface, so the only way that you can know where they are is to pay diligent attention to the charts.

I really have to take my hat off to Captain Cook who sailed these waters with no idea what lay beneath. It is a wonder that the Endeavour only suffered one serious accident here. Bligh also passed through in his open boat after having been set adrift by the mutineers on the Bounty. We passed a few of the islands that he stopped at on his epic journey from Tahiti to Indonesia, a feat that he achieved by navigating entirely from memory.

Those men were giants.

One thing that Bligh and Cook didn’t have to contend with were the ore freighters which continually forge their way up and down the coast. With a good chart, it is possible to thread a large vessel through the reefs in any number of ways, but the maritime authorities have now designated a few specific routes and have made it illegal for commercial vessels to stray from them. On the one hand, this guarantees safe passage for the ships without fear of encountering an unmarked reef, and it means that we always know where they are likely to be, and where they will be heading. On the other hand, the designated channel is often the only reasonable route through, creating pinch points where all vessels, commercial and private, must come together. This is especially exciting at night when you are tired and alone on deck and find that your fragile cockleshell is suddenly the focal point of three enormous cargo ships.

We planned a route that largely avoided the shipping channels in the daytime, but which used them at night when we could take advantage of their navigation beacons.

The days passed and we settled into shipboard routine. The sailing was generally easy, although the trades tended to blow harder at night. In the day, they sometimes died right off, or we’d be hit by a squall, but we made good time and rounded Cape York at around three in the morning of the fourth day.

Cape York is the northenmost tip of mainland Australia, and a milestone on our trip. It gave us an immense sense of achievement to have made it all the way up the east coast. We had now turned the corner, and from now on would be sailing into the sunset.