Each cabin complex on the Three Capes Track has an identical dorm setup, so every night I was sharing with the same people in a carbon-copy of the same dorm cabin. As usual, I had claimed the bunk that nobody else wanted, in the darkest corner farthest from the door, which I crawled into like a yacht’s berth. This gave me my own corner of darkness while the rest of the guys were bumbling around with their bright head torches.

I am sure that head torches are wonderfully useful for those who choose not to let their eyes become accustomed to the dark, but I find them annoying in company because humans are always moving their heads, looking around, momentarily distracted by any noise or motion, and shining their lights into the eyes of anybody they want to talk to. At least with a small pencil torch, it remains focussed on the task in hand, and doesn’t bother anyone else.

I woke as usual six hours after going to sleep, in this case at one in the morning. Rather than get up, I just lay and listened to the wind hammering past outside. The forecast was for a blustery day with 50km/h gusts, and it certainly sounded like it as the occasional flurry of rain pattered on the tin roof.

By seven, I was up and about and making Aeropress coffee. What a fine device this is; lightweight, neat, unbreakable, and capable of quickly extracting every last millilitre of caffeine from a few spoonfuls of grounds. The second-most common comment on my travel kit this week has been, “Oh I wish I’d brought my Aeropress too” (the most common comment was, “Oh I wish I’d brought wine and rum too…”)

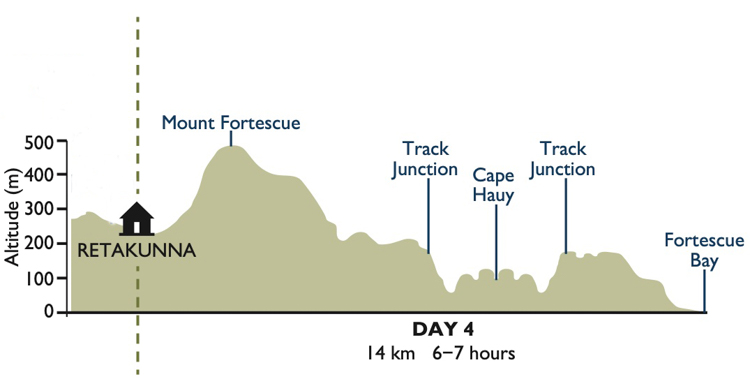

The fourth day of the Three Capes Track is acknowledged to be ‘the hard day’. Not only does it begin with the climb to the top of Mount Fortescue, a vertical rise of just under 250 metres, but it also has the psychological stressor of a scheduled bus waiting at the end of the walk to take us back to Port Arthur. We had booked on the later of the two buses, but nevertheless, the timetable was a niggle at the back of the mind.

There was rain in the cold and blustery air. We donned our waterproofs and set off. The showery weather matched well with the ecology of this side of the mountain, which tended to drippy rainforest and ferns and moss.

The climb wasn’t as bad as advertised, although there were a lot of steps and it got a bit tiring. However, there were many mosses and ferns to look at, and when we finally got to the top, good although misty views back to yesterday’s Cape Pillar.

The rain forest environment was quite different from the Banksia and She-Oak ecology that we had experienced on Cape Pillar. There were no Spring flowers here in the gloom, but instead an abundance of ferns and mosses.

We followed the path across the top of Mount Fortescue, and then steps leading down the other side. Abruptly, we emerged from the rain forest into young stands of Sassafras trees

From here, we quickly dropped to a cliff-side path with the more familiar impenetrable jungle of bush plants, scattered with Spring flowers.

The rain had died off, but now the wind picked up. It got pretty blustery out on the exposed rocky outcrops.

Most of the Three Capes Track is private, in the sense that Parks & Wildlife only allow ticketed groups of 50 trekkers at a time, one group per cabin. The only faces that we have seen for the past three days have been familiar from our time on the trail and in the communal areas of the cabins.

The ranger at Retakunna had explicitly warned us that, near the end of Day Four, the Three Capes Track joins the public track to Cape Hauy. He mentioned that many people like to leave their packs at the junction and pick them up on their return, but pointed out that we should be mindful that – if left – they wouldn’t be as secure as we had gotten used to, because there would be other people about. In fact, when we reached the junction and encountered our first group of day-walkers, it was quite a shock to see the first face “not from our village”.

Most people left their packs anyway, wrapped in plastic to confound the currawongs, which apparently are prone to figure out zips and buckles in their quest for food. I carried mine anyway, for the same reasons as yesterday.

The wind was still gusting, but the weather was warm. The track to Cape Hauy is beautifully constructed of local stone, mainly in the form of steps. It was very pretty, but daunting to find that, whenever you turned a corner, there was more track stretching away to the horizon.

We followed the path until it wound its way to the summit of Cape Hauy. Buffeted by the wind, we stood and admired the dolerite stacks, the views, and some passing whales. Since Cape Hauy is a public area, there is a little guard rail around the top, something that has been deliberately omitted from the controlled parts of the Three Capes Track. Leaning on the rail, facing the mass known as the Candlestick, you can look down on the Totem Pole, popular with climbers.

The ascent of Cape Hauy really marks the end of the Three Capes Track experience. From here, it is but a gentle return to sea level at Fortescue Bay.

It had been a pleasant experience. Hardly a trek, more of a gently curated four-day amble through the bush. Parks & Wildlife have struck a careful line between tourist attraction and introductory hiking experience, with plenty of interesting tales without dumbing anything down. The paths and boardwalks are a necessary evil which insulate you and hold you aloof from the nature all around, but this is to some extent offset by the deliberate lack of signs, fences and guard rails away from the trail, which would otherwise detract from the wide sweeping vistas. The feeling of being part of a small nomadic village was a pleasant surprise, and enhanced the notion of being away from the stresses of civilisation.

Even though we’d booked ourselves onto the late bus, we made it back to the Bay in time to catch the earlier one, but unfortunately that vehicle had been run off the road by a logging truck. Nobody was hurt, but the bus was now bogged in the roadside verge and couldn’t be moved. Pennicott Adventures did a great job of prioritising the walkers who needed to catch onward services, and used spare buses to ferry us all back to Port Arthur, tired but in good spirits.