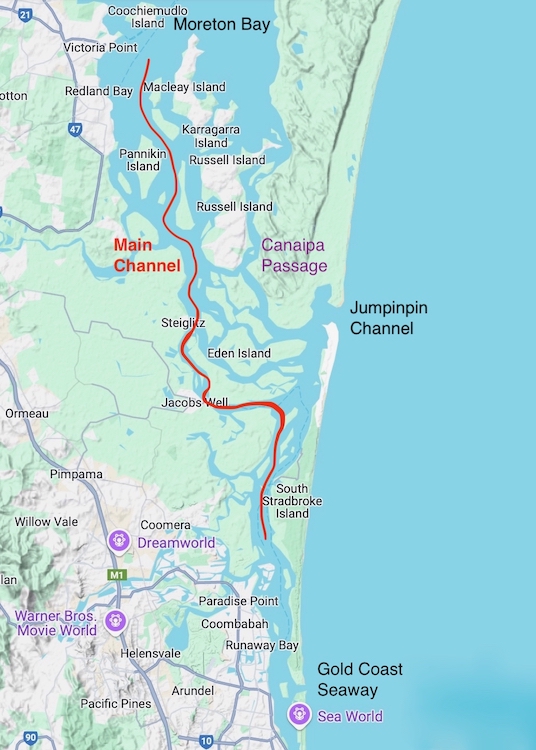

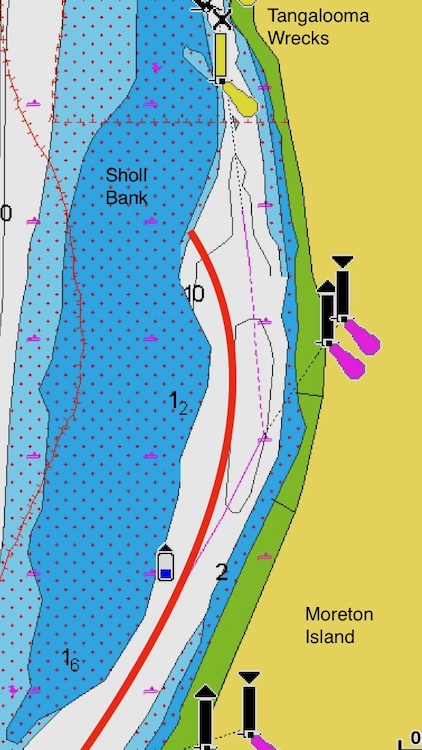

We ate dinner at anchor on our new yacht Vestlandskyss, after motoring south down the Main Channel to the Gold Coast from Moreton Bay in Queensland.

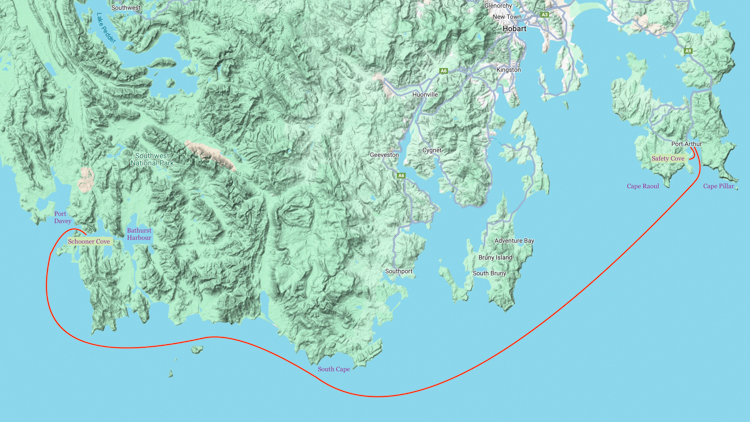

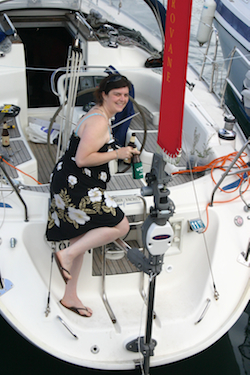

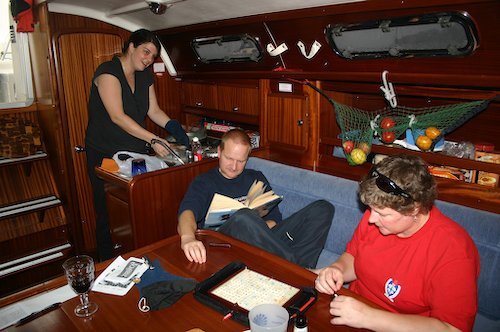

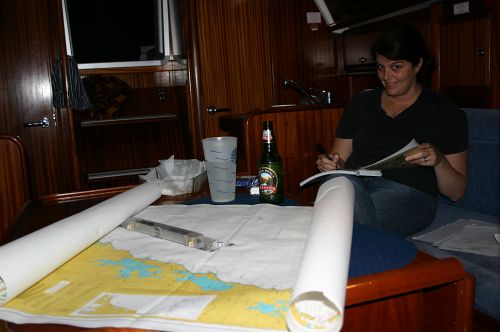

Ahead of us we had planned three days and nights of continuous sailing, to get her even further south, to Pittwater in New South Wales. Aboard were Bronwyn, Brendon, myself, and our nine-year-old daughter Berrima, who had never experienced a passage before.

After dinner, we motored out of the Gold Coast Seaway in an exciting and bouncy bar crossing.

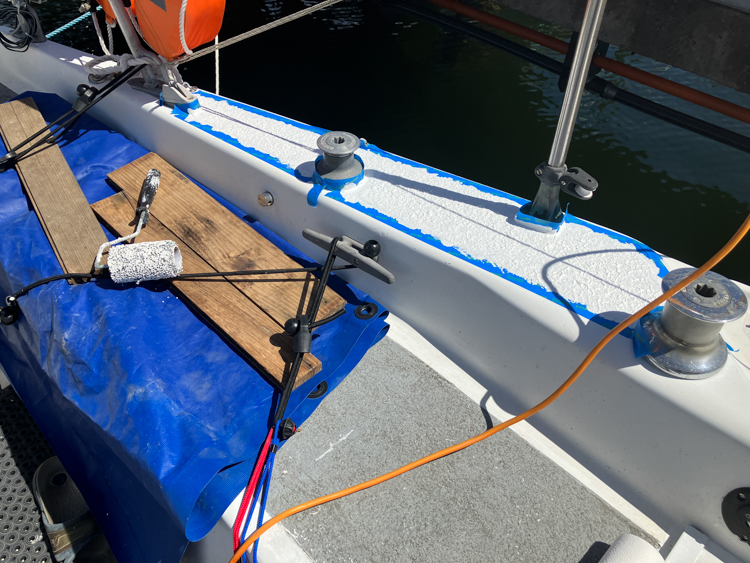

Once out of the heads, we hoisted a full main and a staysail. We’ve never had a boat with a cutter rig before, so we were interested to see what it was like to have an extra sail forward. The staysail stabilised the boat without the tugging that you get from a foresail in a brisk wind, so we gave it a thumbs-up and faced the fall of night with good cheer.

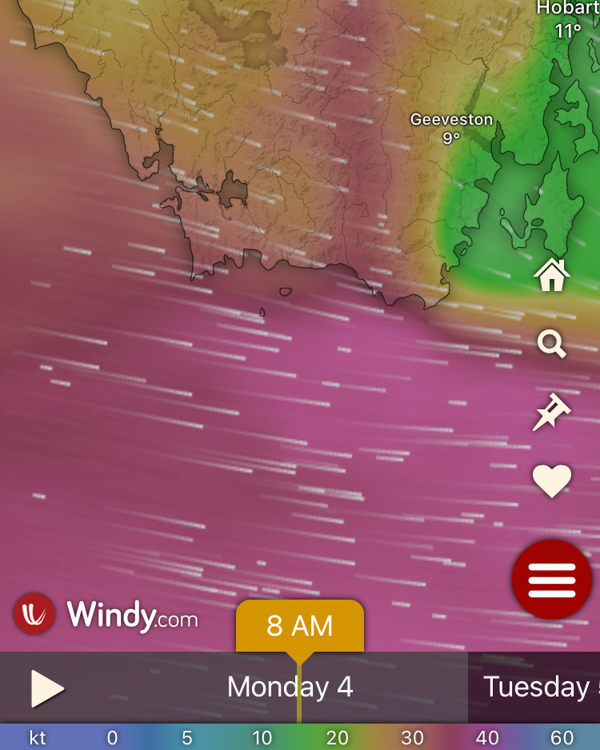

As the sun set, we realised that we weren’t experiencing the forecast easterlies. Instead we had 18-knot southerlies and lightning storms over Gold Coast. We put a reef in the main, and Vestlandskyss picked up the pace, sometimes exceeding 9 knots.

As the night drew in, though, the wind became patchy, with frustrating circling winds of less than 9 knots. What gusts there were, were on the nose, taking us on one occasion to 10 knots speed over ground, but we weren’t seeing the forecast 12 knot nor’easters on which we were, in a very real sense, relying on to move us out into the Eastern Current and then south from Queensland to New South Wales.

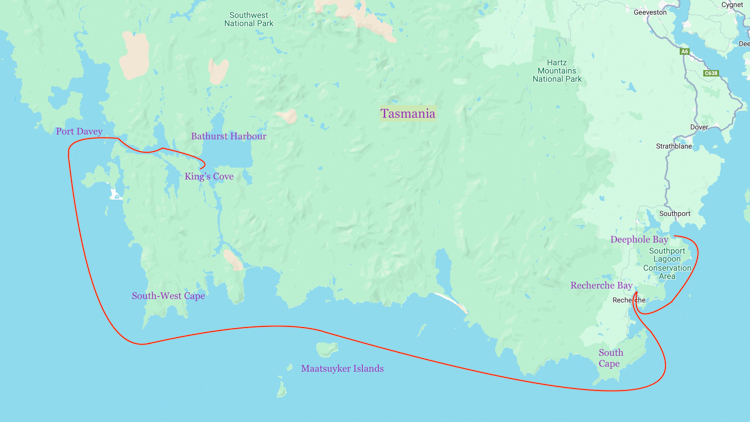

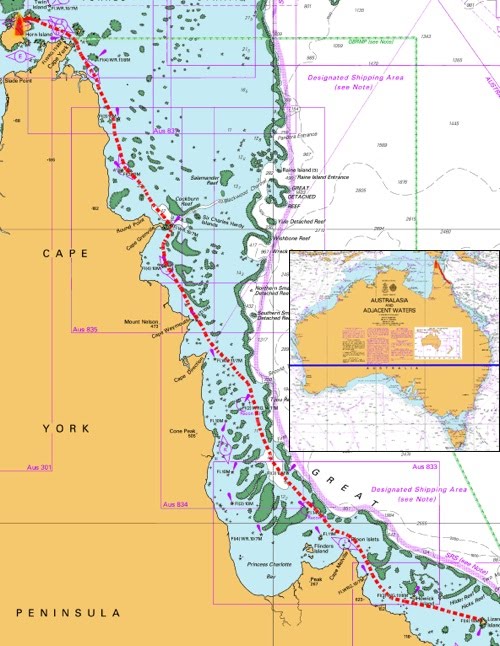

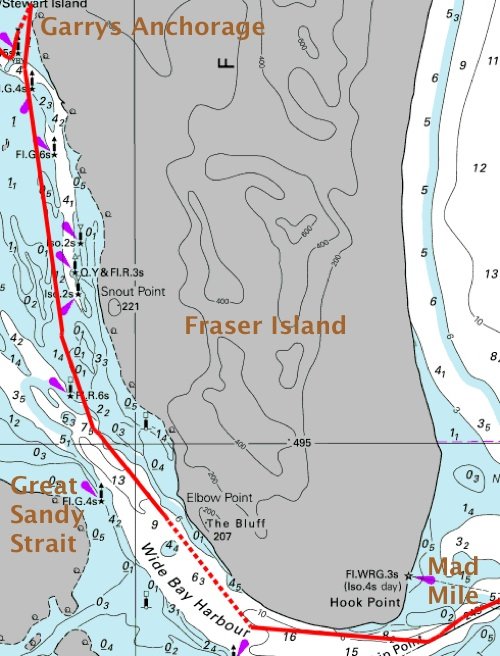

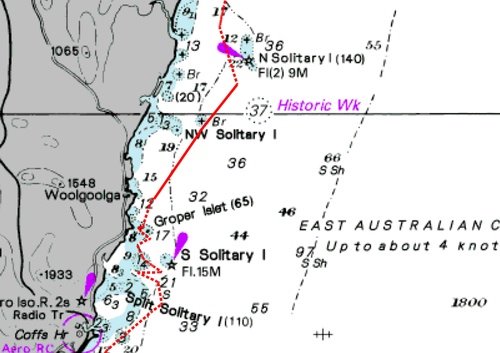

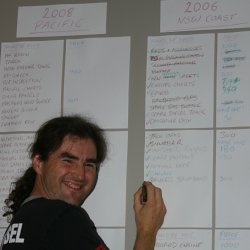

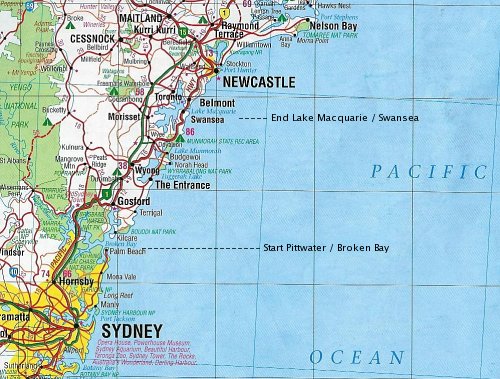

The Eastern Current can give a boost of over two knots to yachts heading south, but its exact location relative to the shore is subject to change. I used Windy to forecast the edge of the fastest part of the current, which was currently about 20 miles out to sea, and then plotted a course to suit. Our plan was to get far enough out into the current to get a good boost down the coast.

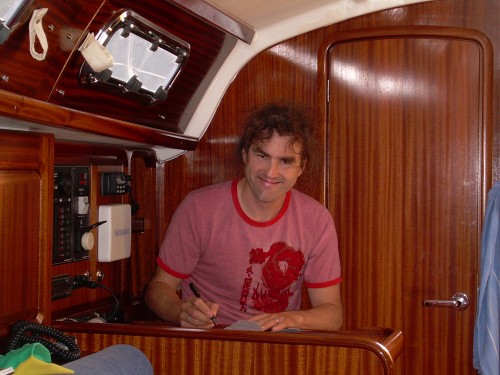

We worked out a watch system, and found that gybing Vestlandskyss with the preventer is a gentle and easy task, settling into a routine of gybing back and forth to try to keep the light quartering winds as useful as possible.

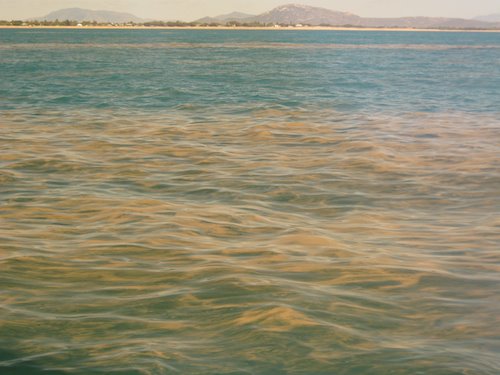

The forecast steady southerly tail-winds never came. They were still showing in the weather models as prevalent right over our position, but not in real life. We decided that we would motor whenever the Speed Over Ground dropped below 5 knots (which would equate to about 3 knots of real speed, accounting for the Eastern Current pushing us south). We motored. The winds didn’t come. We motored some more. We put away the flogging staysail, and started to fret about diesel.

On the plus side, we had albatross and petrels and a pod of orcas.

On the negative side, the wind often died almost completely to leave us motoring through a quartering swell, which is nobody’s idea of a good time. I for one was feeling seasick, and of course it was me that forgot to bring the seasickness tablets. A couple of us threw up over the side.

Then, finally, we caught a rain squall that had us breezing along at 7 knots on a single-reefed main alone, for a whole glorious hour.

Then it was back to watching the wind indicator spin round and around. Occasionally, it rained.

Early in the morning, a big rain squall came through. It was very, very wet. An empty coffee cup on the deck was half full of rainwater in the first fifteen minutes. It did bring a nice wind, though, so Brendon and I stayed out and got soaked to take advantage of it.

A little later, the blessed tail-wind finally materialised, pushing the yacht to the south, floating along in 11 to 18 knots of following breeze. I managed to keep some plain food down, and went to sleep for five hours.

I was woken by the sound of Bronwyn starting the engine because the wind had died again. The diesel tank was now showing only a quarter full, and we contemplated refuelling at Port Maquarie, but it has a shallow bar that only opens up on a rising tide. If we made our way out of the Eastern Current and towards the coast, we would lose our boost and still have to wait bobbing at sea for three long hours before we could attempt the crossing.

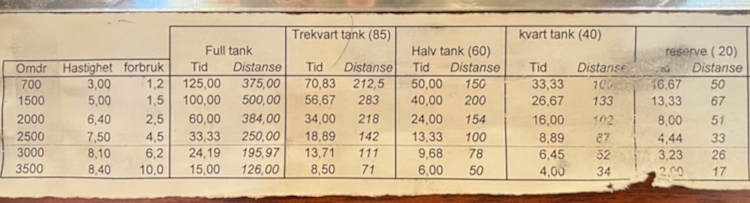

There were plentiful notes from the previous owner about how long Vestlandskyss could motor at different RPM and tank levels, and these gave us confidence that we had another 102 miles in the tank. At this point we were passing Laurieton and were 80 miles from Nelson Bay, which we know from experience has an easy bar and ample fuel docks.

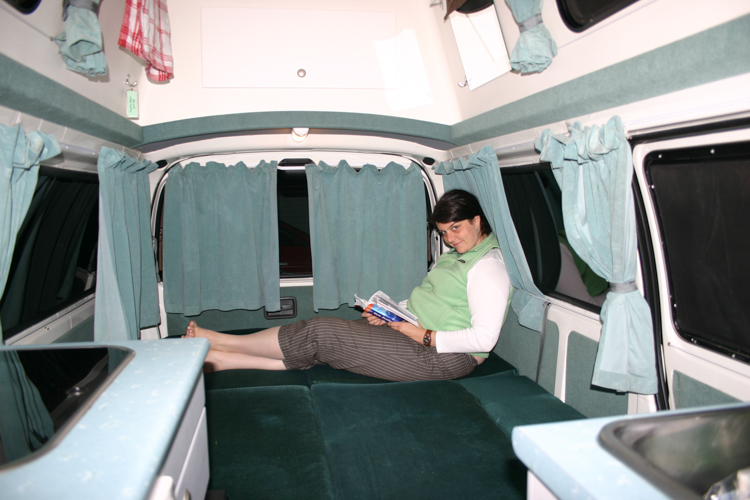

We had already motored for most of one night. It would take us a second full day and evening to get to Nelson Bay, and then a third day to get to Pittwater. We were tired and more than a little seasick, so we agreed to anchor in Nelson Bay and get some welcome sleep.

Stranded in Nelson Bay

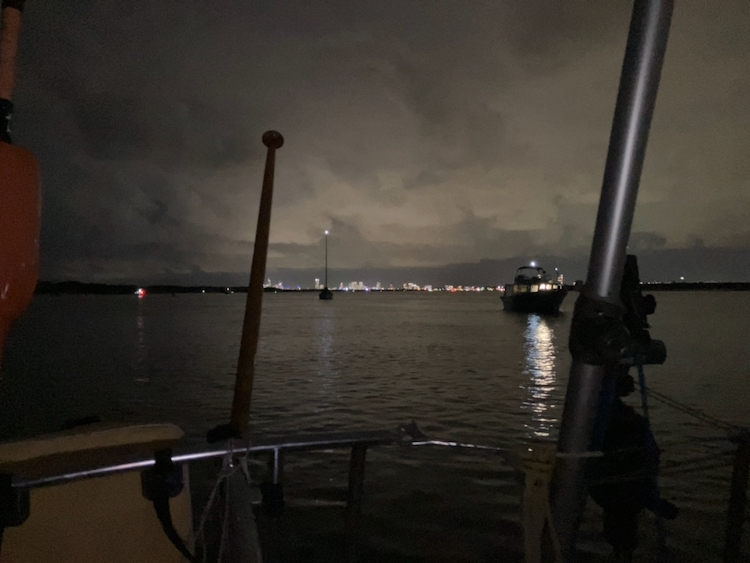

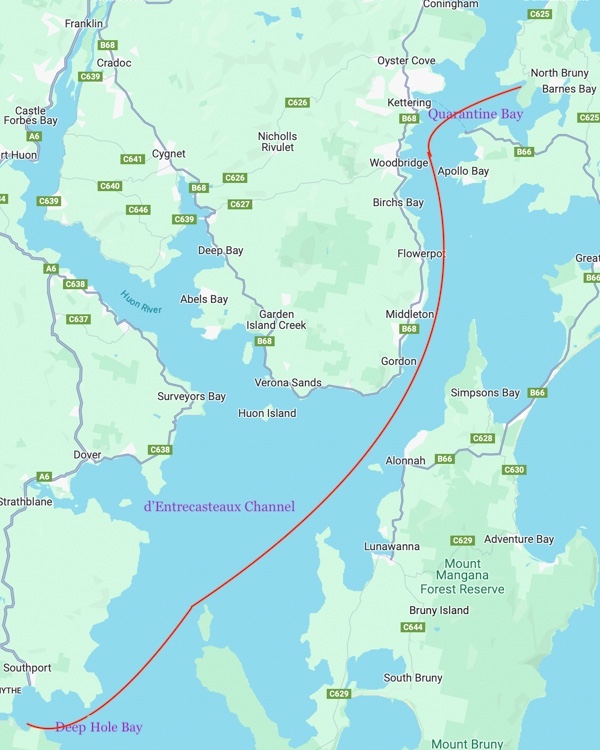

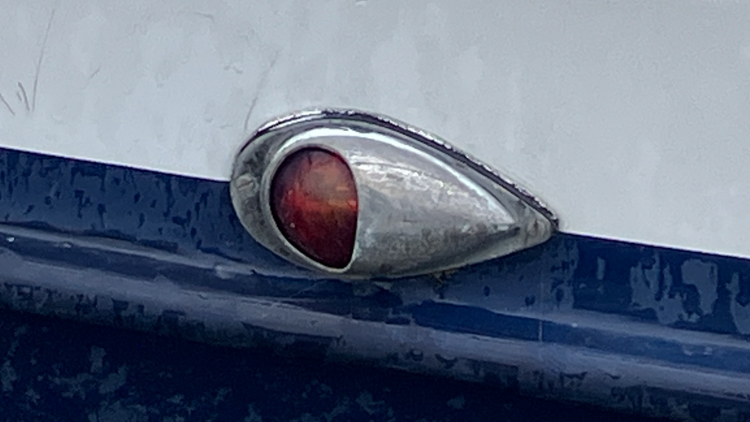

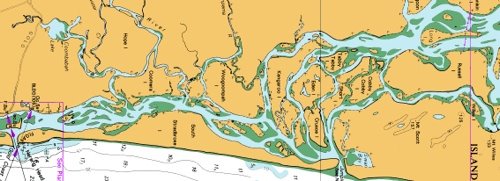

Night fell, and we continued to motor until finally we rounded Boondelbah Island and could see the red white and green leading light beaming out of the entrance to Nelson Bay. The wind started to pick up just then, and the 3 metre shallows – not really a bar – got quite lumpy. Then we were through, chugging into the moonlight shadow beneath Yacaaba Head.

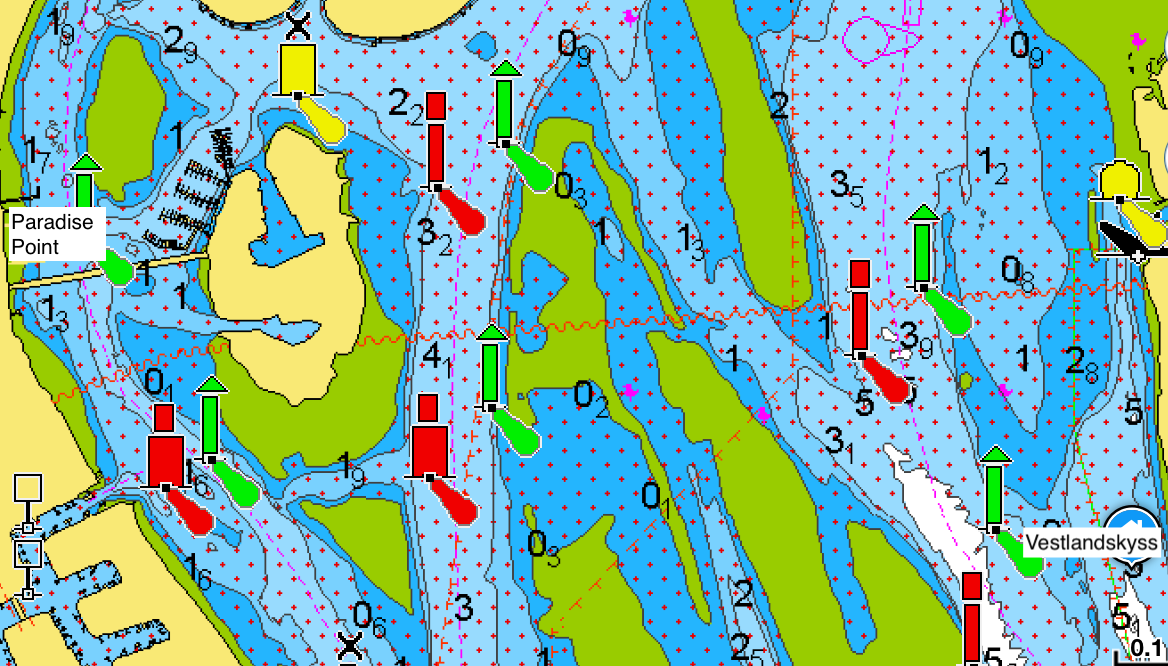

The Speed Over Ground dropped. That was odd, had the opposing tide picked up? I cranked up the power and we continued in, taking a turn to port to avoid charted sand-bars and to run up the southern shore toward – hopefully – some courtesy moorings, currently hidden in the darkness. It was really hard to see the dim and distant channel markers, but the cockpit plotter always knew where we were, and we carefully felt our way along the deepest part of the channel in the dark.

The SOG dropped again. Had the tidal flow increased that much? And then all became clear as the engine gave an apologetic ‘huff’ and stopped altogether as the fuel ran out.

We were out of fuel, in the dark, drifting toward a lee shore without any sails up.

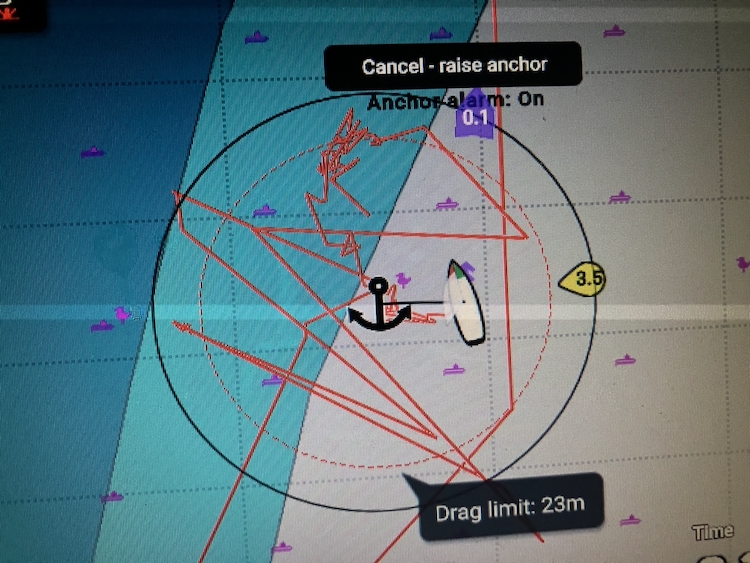

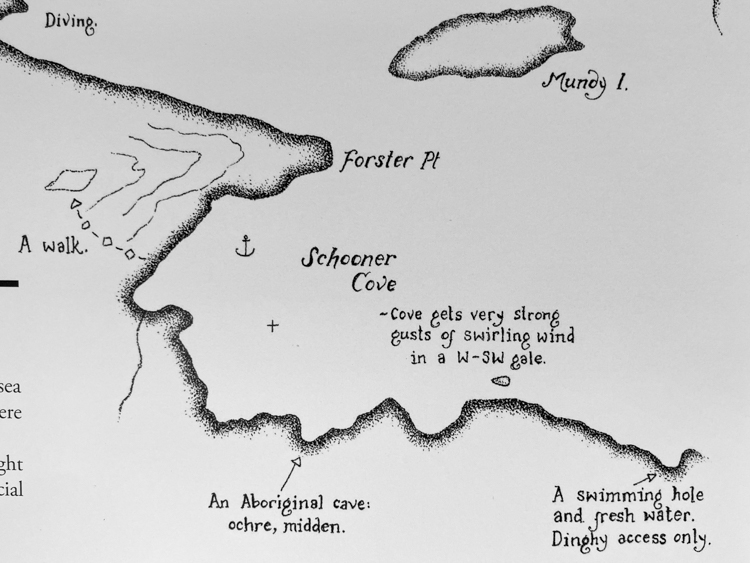

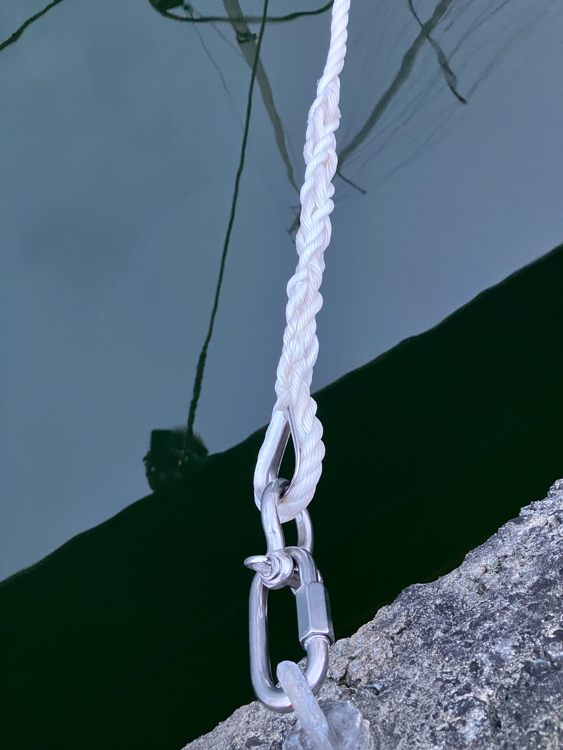

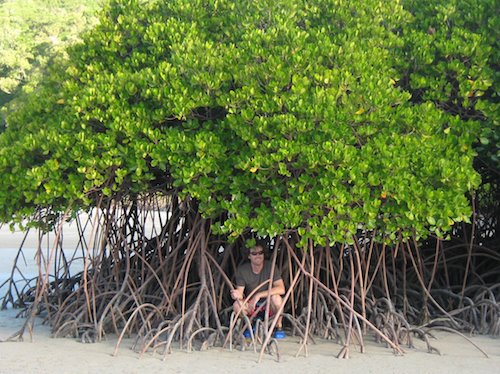

It could have been worse. We were being pushed by the wind toward Little Beach, where the chart said the water was relatively deep with a sandy bottom. The outgoing tide was pushing us to the easterly end of the beach, away from the markers and the jetty. We had just enough steerage left to point the bow at the shore, and Bronwyn held the course while Brendon went forward to ready the anchor.

I was poised to hoist the foresail into uncertain winds if it all went wrong, but we calmly and gently drifted closer, and closer, until we reached 8 metres of depth and Bronwyn said ‘go for it’. The chain rattled out, and we stopped dead in the water, a couple of boat-lengths from the beach. We had arrived.

While Brendon and I assembled the dinghy on the foredeck, Bronwyn got on the phone and cajoled a taxi to come and take me to the nearest service station so that I could get some diesel. She also rang the service station to check that they had clean jerrycans (to keep the taxi-driver’s wife happy), and the local Marine Rescue for advice on the stability of our current anchorage. Marine Rescue were cheerfully optimistic, so I took the tender to the jetty where the taxi was already waiting, and within half an hour was back with fifty litres of fuel.

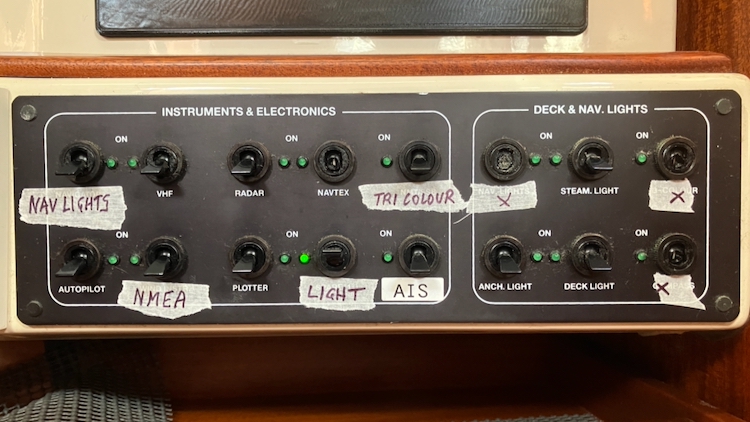

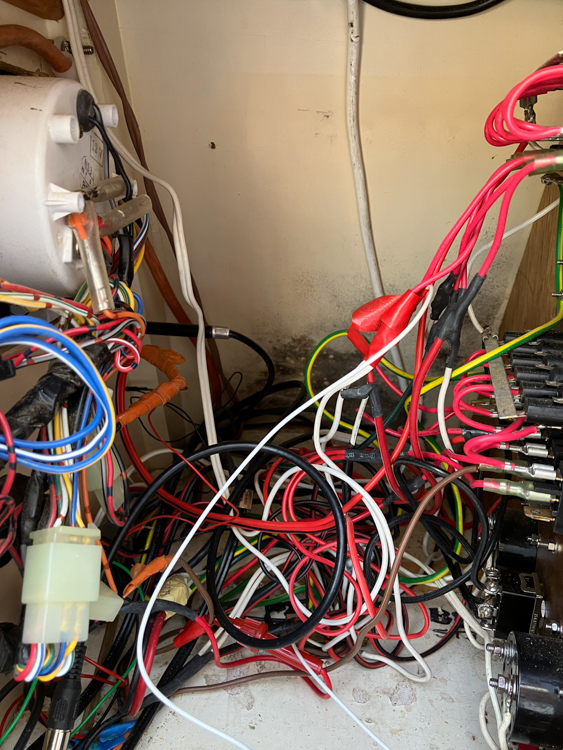

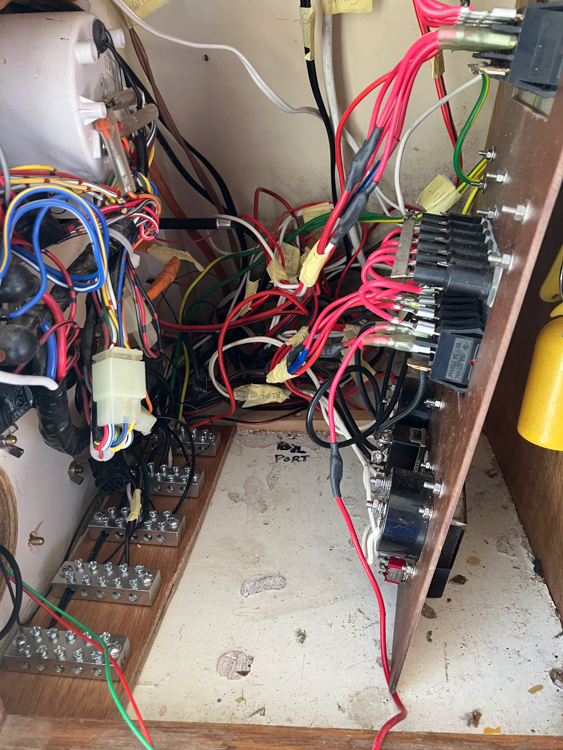

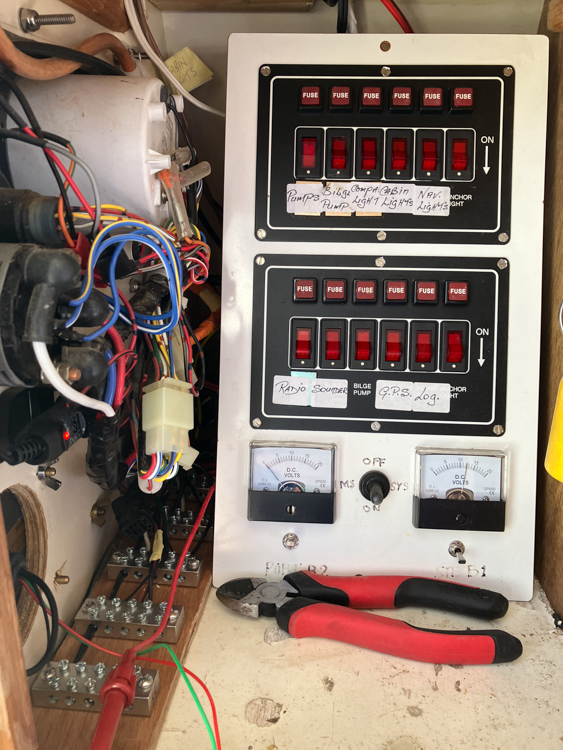

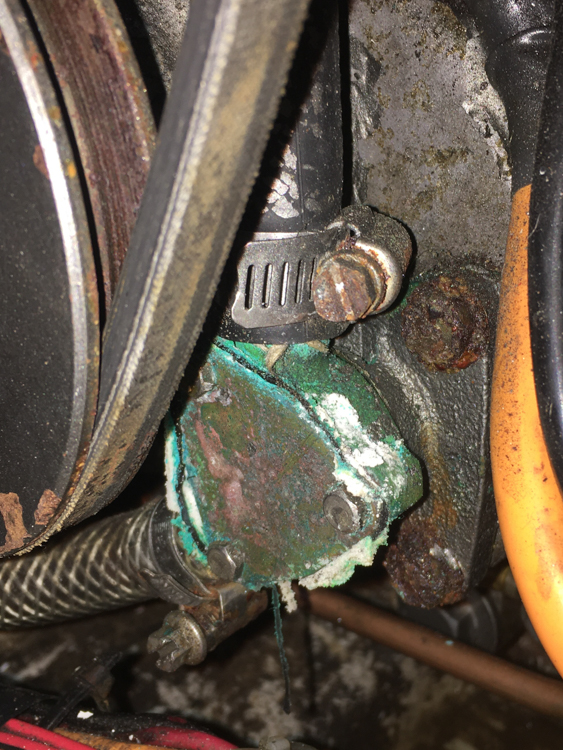

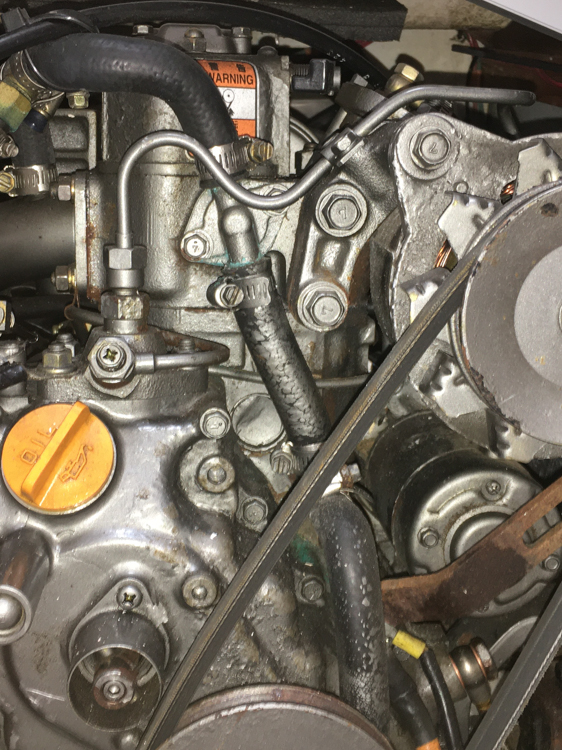

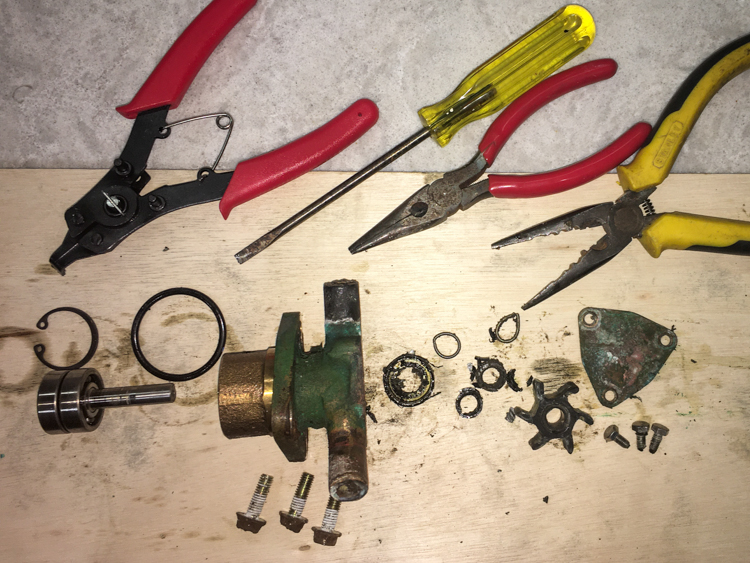

We put half of it in the yacht tank, and prepared to start the engine. I was pretty certain that it wouldn’t start without bleeding, but gave it a go anyway just in case. It turned over but didn’t fire, and then suddenly stopped turning over at all, as if the starter battery was flat. This had happened once before, but on that occasion the battery had changed its mind and decided to fire after all on the third try. This time, there was nothing but a dry click.

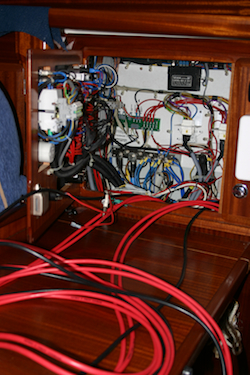

I had noticed a box of spare high-current cables in one of the lockers, so jump-started the cranking battery from the LiFePO4 house bank while Bronwyn cranked the engine. There was now plenty of power, but still no ignition.

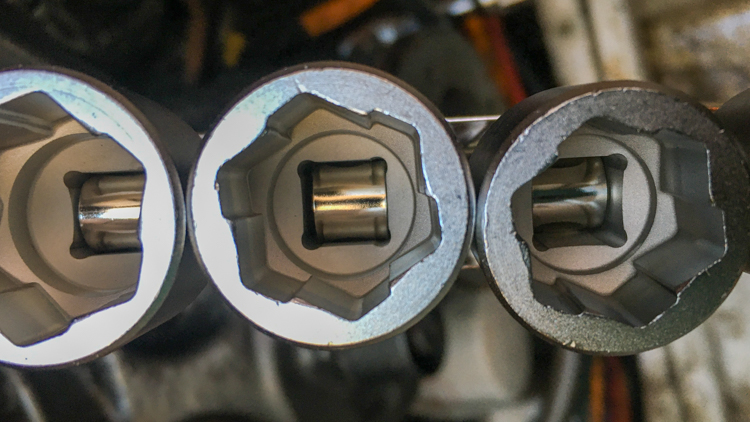

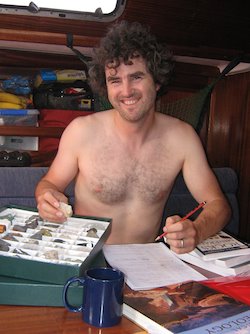

I undid the bleed valve and we started manually pumping diesel, but neither fuel nor bubbles emerged. We pumped for quite some time but my mind was blank. Realising that I was very tired and still a bit seasick, I downed tools and we all went to bed.

I was woken next morning by a phone call from Marine Rescue checking that we were all OK. They’d been monitoring our position on AIS, and the boat had not moved at all in the night. We briefly discussed where I could get a mechanic if I needed one, and then I returned to the engine.

Rested and clear of mind, I had no trouble bleeding the fuel filter. Seasickness is a subtle thing. I cracked the injector lines, turned the engine over a few times, and then started her up, which woke the crew.

She ran sweetly, and we motored up the channel to Peppers Anchorage, where a berth was waiting for us.