The longest arm of the sprawling entity know as the Trans-Siberian railway was built to connect Moscow to Japan via the port of Vladivostok on the eastern coast. However, we had chosen to head south from the major junction at Ulan-Ude, boarding the Trans-Mongolian Express which travels down into Mongolia and then on to China.

We had been travelling through Siberia for almost a week. The restaurant car had run out of food, but we had been buying supplies from platform vendors along the way. This had worked just fine for the first part of the trip, but as we approached the Mongolian border the vendors had completely dried up. For some days we had been living on ice cream, beer, and some biltong that was left over in our luggage. By the time we reached the border at Naushki our stomachs were complaining loudly.

We knew that 215 minutes had been set aside for customs formalities on the train, so we sat quietly waiting for the customs officers to arrive in our compartment, wondering if there was possibly any nourishment to be had from the curtains, or perhaps from our boots. When the Russian emigration officials arrived, we glumly handed over our passports, to be cheerily told that because we didn’t have any documentation, we were now free to leave not only the train, but the station.

Not pausing to argue with this perhaps unique official viewpoint, we ran for the door and joined the stream of hungry travellers barrelling down the platform. A farmer’s market had been cleverly set up just outside the gates, and we descended on it like locusts. We then spotted a little café where I laid into a very satisfying meat borscht followed by a stack of pork chops and onions. Fantastic.

After a couple of hours we got back on to the train and were handed our passports. The train moved about fifty metres and stopped. A phalanx of Mongolian immigration officers boarded and began to take the train apart, lifting the floors, pulling down the ceiling panels, and checking under the seats and on the luggage racks. Presumably they were looking for stowaways. Only afterwards did they pay any attention to the passengers and their documents.

I was quite relieved about this, because due to some apparently needless intransigence at the Chinese embassy I had my Russian visa in one passport and my Mongolian and Chinese visas in another one. I had not been looking forward to explaining why I had two passports, because dual nationality is not widely understood in many otherwise civilised countries, but now that I had already retrieved my Australian passport I simply handed over my English one and nobody knew the difference.

Mongolian immigration kept us up well past midnight, but finally the carriage settled down to sleep. For the most part, anyway: the two conductresses who run our carriage spent much of the night running up and down the corridor shouting and laughing and randomly opening and then slamming our compartment doors. I can only think that this was some kind of payback for us keeping them awake during our night-time parties (see my previous blog entry).

We had set our alarm for breakfast and woke very confused because although the train was under way, nobody else was stirring. We eventually realised that the train had switched from Moscow time to Ulaanbaatar time. Because the Russian section ignores all the intervening time zone changes, we magically jumped five hours at the Mongolian border, and we had inadvertently set our alarm for 03:00 train time. Back to bed.

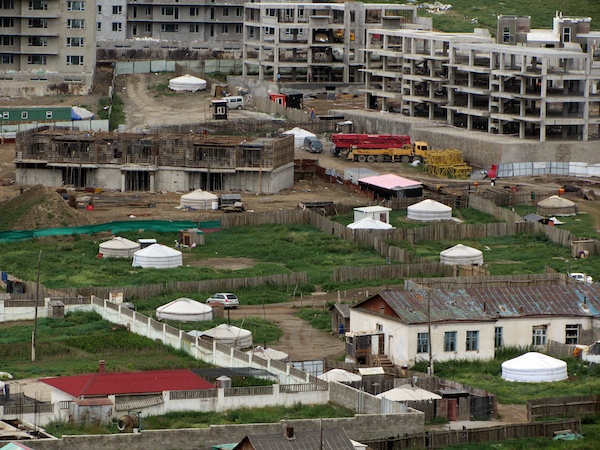

At 06:00 we woke to cloudy skies above fields of fenced corrals, each containing a white canvas yurts (known as gers in Mongolia), interspersed with what seems to be stalled Soviet-style construction. We had heard that, since self-determination from Russian rule, 70% of the Mongolian population have abandoned their enforced ‘western’ life-styles and have returned to their traditional nomadic living. There was plenty of evidence of that from the train.

Mongolia’s recent history is not a particularly happy one. The country was ruled from China for some years until it gained a spurious sort of independence by allying itself with the USSR. Unfortunately the only difference in the new regime was that Mongolia’s vast mineral wealth began to head north on the Trans-Siberian railway instead of south. Neither the Chinese nor the Russians wanted to build processing plants on what was effectively occupied territory, preferring instead to transport the cheap raw material back home, where local industries would benefit from processing the low-value ore into high-value commodities.

On gaining true independence in the nineties, Mongolia continued to use the Trans-Siberian to ship unprocessed ore because it didn’t have the cash to invest in its own processing plants. However, we hear that they are making a deal with Australian mining giant Rio Tinto who, in exchange for copper and gold mining rights, have agreed to building processing capacity on site. Hopefully this will start a renaissance in Mongolian fortunes.

We disembarked hungry and dirty in Ulaanbaatar. Our first stop was – blissfully – a local spa where we showered and I had a chance to shave my increasingly unruly beard, before demolishing a buffet breakfast of rice and fruit and eggs. Only then were did we feel ready to go out and sample the delights of the big city.